Introduction

To hear is to forget, to see and hear is to remember, and to do is to understand.

Confucius

This module takes you through the process of producing a report from conception through to proofreading. You will learn by doing rather than by reading about how to do.

The module is presented in three sections. In the first section, Writing the First Draft, you will apply the writing framework discussed in Module 1 to the task of report or proposal writing. You will determine a statement of purpose for your report or proposal and do an in-depth analysis of its intended readers. You will learn to analyse guidelines and other documents to achieve Council of Europe expectations for the document you are planning. You will then organise your material and produce a preliminary draft. The second and most substantial section of the module, Writing Key Sections, will take you through the fundamental skills of report and proposal writing. Using examples from the Council of Europe, you will work on writing specific components of reports and proposals. The final section, Editing Your Document, focuses on the final tasks needed to complete your report or proposal and make it ready for distribution. This section lets you apply what you learned in Module 1 to a single text.

At times during the preparation of your document, you will be asked to reflect on the process that you are undertaking. You will keep a record of the time you take on the various steps and your observations about the process. This time-tracking will help you work out the best way to approach future similar tasks. Throughout the module, you will have the support of your tutor.

Module objectives

On completion of this module, you should to able to apply the principles and strategies of effective writing explored in Module 1 to report and proposal writing. Therefore, by the time you have completed this module, you should be able to:

- develop a strategy for structuring your report or proposal;

- adapt the writing process described in Module 1 to the development of a report or proposal;

- apply brainstorming and drafting techniques to the writing of a report or proposal;

- arrange your ideas to bring out main points;

- recognise the essential components of a report or proposal;

- analyse reports and proposals at the Council of Europe and recognise their differences.

Assignment

You will demonstrate your competence by the production of a work-related report or proposal that meets the performance criteria stated in the assignment page.

You are encouraged to develop your report in sections as you work through the module. By the end of the module, you will have already drafted your complete document, and you will be ready to revise based on the feedback from your tutor. As you work through the module, you will also create some planning documents that will help you to develop your report or proposal in a systematic manner. These documents are part of your assignment. You are asked to submit some of them to your tutor before you have completed your report. Reference will be made to these documents in the Assignment Preparation Tasks.

Communicating with your tutor

You are encouraged to stay in contact with your tutor as you work through the second module. You will be submitting preliminary documents as you write the report or proposal. You’ll also see some prompts as you work through the module encouraging you to get in touch. These prompts are not requirements, just reminders that one of the best ways to ensure your progress is to stay connected with your tutor.

Assignment preparation task 1: Choosing a report

Before you begin work on this module, choose a writing task to work on throughout. As you are choosing a project, take a quick look at the assignment requirements for this module. This report or proposal should be work-related and ideally a current requirement of your job.

The ideal type of assignment report has an anticipated length of somewhere between six and 12 pages. If you think it will be longer or shorter contact your tutor to ensure the scope is appropriate. If you are writing a proposal typically you are constrained by the length requirements of the funding agency. Contact your tutor to discuss what is required and determine if the proposal is appropriate as an assignment for this course. You can choose to submit an entire report or proposal if it falls within the recommended length or you may decide to work on a section of a report: for example a chapter of a longer report. Either choice will be appropriate for this module.

Requirements for report writing vary across the Council of Europe. For this reason, the module content does not focus on specific types of reports or proposals. The purpose of this module is to allow you to apply general principles of effective writing to any type of report or proposal. You are expected to follow the guidelines or conventions of your department or working area, and the module includes a discussion of things to look for in examples of the type of document you are writing.

Keep in mind though that a degree of flexibility is possible. The most important feature of your assignment is that it is relevant to the kind of work you do. Please do not hesitate to contact your tutor to discuss the nature of the document you would like to write.

SECTION 1: Writing your first draft

Knowing is not enough; we must apply. Willing is not enough; we must do.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Writers at the Council of Europe undertake a range of reporting activities in their day-to-day work. Evaluation and explanatory reports, committee reports, annual reports, mission reports, project proposals, funding proposals: some of these writing activities are relatively straightforward and require little planning. Others are complex and challenging, warranting a multi-step procedure. This section focuses on a procedure for writing complex reports in an effort to equip you with the strategies and skills required for a range of future report writing tasks.

Whether they are simple or complex, neither reports nor proposals are detective novels. You don't have to build to a climax, reveal clues as you go or even keep the reader in suspense. Reports and proposals are much simpler. They are working documents. The sooner the reader knows the plot, the easier it is for everyone. If you keep this in mind, you will find the task of developing an effective document much more achievable.

In this module, we will examine the writing process more deeply by applying it to report and proposal writing in general and to the document you’ve chosen for your assignment in particular. The aim is to provide you with useful tools for all your future writing projects.

Determining your purpose and analysing your audience

You have already explored the notion of purpose in Module 1. We called it your desired response: what you want the reader to do as a result of reading your document. (Click here if you need to refresh your memory of this part of Module 1.)

Who are you writing for? Why? Answer these questions, and you will be ready to write your statement of purpose. To answer them, you will need to discuss the requirements with your manager or whoever else assigned you the writing task. You may need to consult earlier versions of the document (last year’s report, for example, or an earlier proposal) to fill in your knowledge of what’s needed. Continue asking questions until you are clear about the requirements.

A good report shows a strong relationship between its findings, conclusions and recommendations; a good proposal shows a strong relationship between its statement of need and project proposal. These connections create coherence in the document, and they begin with the statement of purpose. Consider this in the context of some common reporting tasks.

Click on "As a result" in the following statements of purpose to see the corresponding purpose of the report.

A progress report

of reading my progress report, my reader will support my recommendation that this project be extended for six months.

The report would recommend an extension and provide support for this recommendation.

A mission report

of reading my mission report, my reader will have a clear idea of the discussions that occurred during the mission.

The report will identify predominant themes of the discussions.

An evaluation report

of reading my evaluation report, my reader will know the reasons for success or failure of the programme under consideration.

This report will allow for the next step in considering the future of the programme that has been evaluated. The report, then, will help determine the future of the programme.

A proposal

of reading my proposal, my reader will fund the [name] project as described in my proposal.

The proposal will provide a strong case for the project, both in terms of its value and feasibility. It will convince the reader to support the project.

Assignment preparation task 2: Defining your purpose

Compose a purpose statement now for the document you will be writing. Remember that your purpose statement should begin, “As a result of reading my [report/proposal], my readers will…”

As a result of reading my report, my readers will…

This purpose statement will help you stay focused as you write. If you find your writing is beginning to stray from your purpose you can always re-evaluate your report, or perhaps you will find you need to revise your purpose.

Assignment preparation task 3: Reflecting on the writing process

From now on, for each assignment preparation task, please record the time taken on any assignment-related activity in your Reflection File.

Save this file in your assignment folder since you will need to return to it as you work through this module.

Assignment preparation task 4: Analysing your readers

Many people may read your report or proposal. When you analyse your readers, we want you to focus on particular types of readers: those who will be reading your report or proposal for the information and ideas it contains. You will have other readers too: in this case your tutor and possibly a manager or colleagues who are assisting with the document. When you analyse your readers, do not focus on this latter group. One way to think of this is that your analysis should focus on your document’s audience. Your manager, your tutor and your colleagues are often not the audience: they are your coaches and cast members who are helping prepare the work.

You will have primary readers, probably including a key decision maker, and then you are likely to have other readers (secondary readers). For example, if you are writing an audit report your primary reader(s) will be those who have the power to implement the changes you recommend. Others who work in the auditing programme might be your secondary readers. Although your focus should be on your primary readers and the key decision-maker, it is wise to keep secondary and possibly tertiary readers in mind.

Complete a Reader Analysis Form introduced in Module 1. You will need to submit this to your tutor with your outline.

Record your impressions in the Reflection File you started with the previous Assignment Preparation Task.

Prewriting

Using your favourite prewriting technique, generate the ideas and content required for the document you have chosen to write. If you need to fill in data for your report or find information to complete a proposal do that data collection now.

At this stage, you may find that you see a sample of the type of document you are writing. For instance, if you are responsible for producing an annual report you should look at last year’s report to note the structure and major sections. The process of analysing earlier versions of documents will be discussed more at the beginning of the next major section.

Do not spend any time polishing this very early draft. What you need to do is make some notes on what is required for the document you are writing. Your notes should be detailed enough to use as a basis for outlining, but they do not have to be in order or polished. You can think of this as the equivalent to a quick sketch an artist might make before beginning a painting.

Once you’ve written this rough draft, open the Reflection File that you created in the previous piece of work. In your Reflection file, make note of:

- the prewriting technique you used;

- your feelings about using it;

- the time it took to do the draft;

- any other details you would like to remember about the process.

This record can be helpful for you later particularly if you keep track during the drafting process of more than one document. You may find that you can work out an average speed per page of draft, and this will help you with your workflow planning.

Organising

Already at this early stage, you have completed three important planning tasks:

- determining your statement of purpose;

- analysing your readers;

- generating some ideas about the content and direction of the document you are writing.

Now you need to get down to the business of organisation. This involves establishing your main points which will become the Level 1 headings in your report.

Remember that when you are preparing an outline using Microsoft Word, it is beneficial to use the Styles’ function to assign levels to the headings. This helps you in two ways:

- it helps keep the document visually consistent, which adds to its coherence;

- it makes it possible for you to generate a table of contents automatically, which saves time.

If you use the Outline view this happens automatically. Do consult your Word help menu, though, if you need more information.

Remember to look at your example document again, if you are using one, as you begin the organising process. Many types of documents are written at the Council of Europe, and there are often expectations for things like section names and headings. Save yourself time and frustration by following the model you have found.

Activity 1: Establishing main points

How do you arrive at these main points? There are a number of ways, and they are all about distilling the essence of what you want to communicate. Here are three strategies to help you. Think about the report that you are planning to write. If you are struggling to focus try one of these strategies. You can type your answers in the fields below each strategy.

Imagine you meet a very important person in the elevator who asks you about your work. You want to tell this person about the document you are writing, but you only have time to mention a few key points. What would you say?

Ask yourself this: what is the absolute minimum that you want your reader to know if you know they are just scanning the document?

Imagine you have told your reader the title and purpose of your report. What questions would you expect them to ask? The questions you anticipate can form the basis for your headings.

Achieving flow through organisation

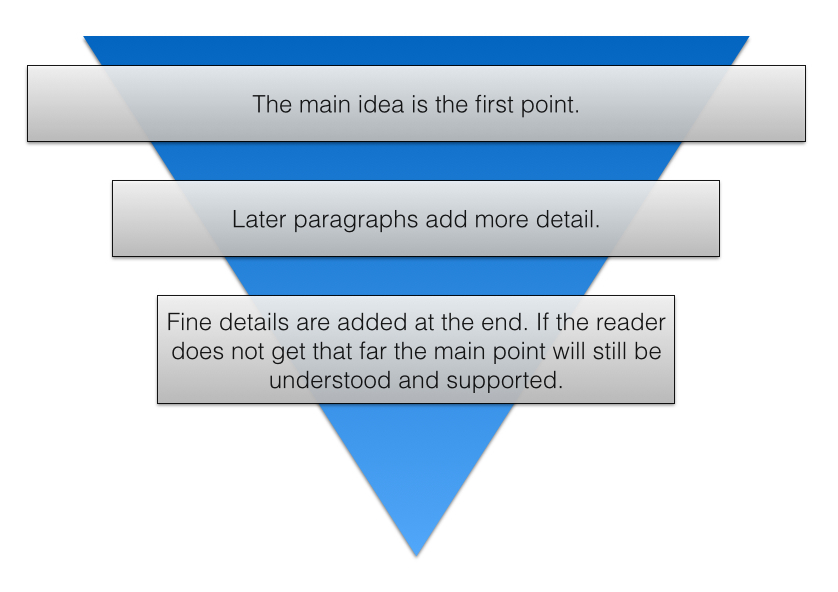

Writing a report is similar to writing a news story. In both cases, the reader wants to get the most important information first. This tempts the reader to read further – perhaps to click for more information in a news story – and assures that if they do not go further they will know the most important thing.

When you glance at a news website, you immediately know what each story is about. The title tells you that, and the few words below the title tell you a little more. If you are interested you will click to follow up with more details. From the earliest link, you will know what to expect from the story.

You can visualise this approach by thinking of your writing as an inverted triangle.

There are many applications of this concept from the whole-document level to the paragraph level.

In a report…

Putting a summary first in a report allows your reader to begin reading with a framework on which to attach new ideas. Comprehension or understanding is only possible when there is a bridge between the new and the known. For example, if you have no experience in piloting an aircraft it would be difficult for you to understand a lesson on aerobatics. The summary up front gives you some known information on which to link new information.

In a proposal…

Putting a summary first allows your reader to begin reading with a framework, as in the report. In most proposals, a statement of need at the beginning of the report prepares the reader to understand why the project is important.

In a message…

Beginning your email or memo with an informative subject line helps focus the readers’ attention. It is important to keep your subject line brief: a few words, not a paragraph.

In a paragraph…

Placing your topic sentence at the beginning of a paragraph draws the readers’ attention to the main idea.

Flow and your reader

The flow of a piece of writing affects how its readers interpret ideas. If a document’s organisation doesn’t provide readers with the information they are looking for in an organised way they will lose interest.

The reader does not need, or want, to know about all the steps you took along the way to forming your conclusions. Instead, the reader wants to know what those conclusions are and if you have sufficient logical support for them. What is required on your part is organisation or structuring of your material to express your conclusions clearly and your support for them.

Organisation is based on:

- providing a hierarchy of ideas for your audience;

- choosing the most appropriate order for those ideas.

Establishing a hierarchy of ideas

Level 1 headings become the signposts of your document, with each section heading clearly indicating the nature of the content below it. Depending on the size and complexity of the document, you will need to divide the information under each Level 1 heading into subsections (level 2 headings) and so on.

For example, here is a partial look at the hierarchy of ideas as organised in this section of this module:

| Drafting your document | ||

| Determining your purpose and analysing your audience | Prewriting | Organising |

| Defining your purpose Reflecting on the writing process Analysing your readers |

Establishing the main points Achieving flow through organisation Establishing a hierarchy of ideas |

|

Arriving at a hierarchy of headings; however, is not enough to give your writing flow; information needs to be arranged according to patterns so your reader can see the relationship between ideas. This patterning of information should take place at all levels in the document: whole, section and paragraph.

Choosing an appropriate order

Constructing paragraphs according to various patterns of organisation has been treated in Module 1. There it was treated at the paragraph level. In this module, we will explore patterns of organisation: the section and the whole document.

The document’s purpose and audience should control your choice of a pattern of organisation. Let's look at this in practice.

Activity 2: Ordering ideas

Imagine that you work with the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT). With colleagues, you have travelled to Country X to monitor the situation in prisons and other places where individuals are detained. It is now your task to write the report section on prisons. Because it helps you focus, you write this statement of purpose for your report section: As a result of reading this report section, the Government of X will have an accurate assessment of the prison situation in the country.

You and your colleagues have collected a lot of information about prisons. You have decided on five main headings for the report section:

- preliminary remarks;

- ill treatment;

- conditions of detention of life-sentenced prisoners;

- healthcare services;

- other issues.

Here is some of the information you have received from colleagues. Indicate which section each note belongs in.

| Your response | Answer | |

|---|---|---|

| Prisoners are held in two main buildings, designated as A and B. | preliminary remarks |

| Your response | Answer | |

|---|---|---|

| There are often long delays in seeing a physician. | healthcare services |

| Your response | Answer | |

|---|---|---|

| Some cells are in a poor state of repair, particularly in Building B. | preliminary remarks |

| Your response | Answer | |

|---|---|---|

| Some prisoners report incidents of ill treatment, particularly in denial of services. | ill treatment |

| Your response | Answer | |

|---|---|---|

| Clothing is regularly laundered and appropriate for the season. | preliminary remarks |

| Your response | Answer | |

|---|---|---|

| Life-sentenced prisoners are seldom allowed to socialise with others, except those in the same cell. | conditions of detention of life-sentenced prisoners |

| Your response | Answer | |

|---|---|---|

| It is often difficult for prisoners to arrange to see a medical specialist. | healthcare services |

| Your response | Answer | |

|---|---|---|

| Quality of food provided is reasonably good. | preliminary remarks |

| Your response | Answer | |

|---|---|---|

| Staffing levels are very low. | other issues |

| Your response | Answer | |

|---|---|---|

| Building B houses life-sentenced prisoners and others whose sentences exceed 10 years. | preliminary remarks |

| Your response | Answer | |

|---|---|---|

| Some prisoners have been physically injured by guards. | ill treatment |

Activity 3: Organising sub-headings

Below are the headings for another short report, this one reporting on an ad hoc committee’s visit to a location where many migrants have arrived. Turn the list into a table of contents that reflects the way you would organise this report.

- Recent developments

- History of YYY as a destination for migration flows

- Local and international organisations involved

- Asylum procedures

- Health checks

- Early official responses

- Interception and rescue operations at sea

- Local reception facilities

- History of YYY as a destination for migration flows

- Early official responses

- Recent developments

- Local and international organisations involved

- Local reception facilities

- Interception and rescue operations at sea

- Health checks

- Asylum procedures

This is more difficult than it looks. Once you've arranged the headings and checked the suggested responses, consider the way the report is organised. In your view, was an appropriate organisational pattern selected?

The writer of the report chose to organise it chronologically. History is first, then more recent developments and the current situation. Finally, with the heading “Asylum procedures”, the report looks to the future.

Assignment preparation task 5: Organising

Now that you have had a chance to practise some of these ideas, you can put them into action as part of your assignment preparation.

Using the ideas and strategies in this section, produce an outline for your report. You will need to consider, and document, the purpose and audience, the hierarchy of ideas and the pattern of organisation you will adopt. Follow the example of an earlier version of the document you are writing if that is expected.

The headings in your outline will be the headings and sub-headings in your report or proposal. Make them as useful as possible. Substantive headings like the ones in the preceding exercise make it possible for the reader to grasp the main points of the report by scanning the headings. Substantive headings will also make it easier for your tutor to give you useful feedback about the document’s organisation.

Submit your outline and the reader analysis you completed earlier to your tutor for preliminary feedback.

What to do

Open a new Word document and save it in your assignment folder.

Develop an outline for your report using one of the techniques discussed in this module.

In your Reflection File, record the approach you used and how effective you found it. Also, record the length of time it took for this step.

Drafting

In Module 1, we made several recommendations for writing first drafts:

- concentrate on getting down what you want to say;

- write first and edit later. Try to keep your thought flow going;

- concentrate on capturing a good flow of ideas;

- aim to pick up mechanical and other errors later;

- write your draft as fast as you can and in one sitting if possible. Don't try to write an introduction first or stick to a beginning-to-end structure unless that feels natural.

Some additional points may help you to write longer documents.

- Don't skip crucial steps.

Don't expect to be able to write a final version of your document immediately. Even if your time is very limited, identifying your objective and purpose will help you to create a report more quickly and efficiently. - Control your writing sessions.

If possible plan to write at least one draft of the entire report and be prepared to rewrite critical sections several times. Try to write in uninterrupted blocks of time, and if you have to stop try to break at a point where you know what you are going to write next. This means when you come back to the task, you can reduce the warm-up time before becoming productive again. If time permits wait at least two days after completing the first draft before you begin editing and rewriting. - Use headings.

The drafting stage is a good time to consider your use of headings. Headings improve a long document’s readability and usefulness. Headings are important to both the writer and the reader in long documents. Working on heading levels (main headings, sub-headings, sub-sub-headings, etc.) forces the writer to think about the relationship between the different parts of your document.

For the reader, headings:

- indicate visually how the various parts of the document and the content relate to each other and their level of importance;

- provide guidance through long reports and help readers to identify and skip what they are not interested in;

- break up long stretches of text visually, with the result that a less-daunting reading task is presented to the reader;

- allow the reader to revisit sections of the report easily.

Activity 4: Using headings

Read the following excerpts from a report on a consultation process conducted as part of a child-friendly justice initiative. You will notice various points where an ellipse (…) is included; this indicates that parts of the paragraph have been removed to save reading time.

The excerpt is included without the proper headings. From the drop down lists of headings, select the heading that is appropriate for that place in the report. One of the headings provided is an extra one and does not belong in the report. Note that the list contains both headings and sub-headings, and is in alphabetical order.

Child-Friendly Justice: the Views and Experiences of Children in the Council of Europe

Introduction

The Council of Europe is drafting Guidelines on Child-Friendly Justice in close co-operation with the Programme “Building a Europe with and For Children”. To ensure these Guidelines are informed by the views and experiences of children, the group charged with drafting the Guidelines decided to undertake a consultation exercise across Council of Europe states in Spring 2010.

Method

The primary method used was a questionnaire. This was prepared in association with approximately 30 partner children’s organisations including Children’s Rights Alliance for England (CRAE), the European Network of Ombudsman for Children (ENOC) and Unicef. National organisations were asked to distribute the questionnaire as widely as possible and they were also encouraged to use other methodologies, as appropriate, to gather the views of children especially young children and hard-to-reach groups. …

The response

The national organisations all responded differently to the Council’s request for co-operation. Many distributed the questionnaire widely among schools and community-based settings, while others used it to engage with specific groups, such as those in conflict with the law, in detention and in care. … This data was enriched by a range of focus group discussions conducted with particularly vulnerable groups of children (such as those in detention, refugee children and those whose relatives are in prison), and some national organisations submitted useful reports giving context to the consultation exercise, and providing further information on the impact of the justice system on children. …

Findings

Despite its shortcomings, the process produced rich data on the views and experiences of children in the justice system. This will continue to be analysed and reviewed in the months ahead. The following is a snapshot of what the children told us.

About the children

The respondents ranged in age from a small number of children under 5 and under 10 years, to the vast majority who were between 11 and 17 years, about half of whom were under 15 years. An almost even number of boys and girls completed the Questionnaire. …

Information about their rights

A very high proportion wanted more information about their rights and when asked who they wanted that information from, the majority chose their parents or others in a position of trust. Youth workers, and-to a lesser extent-lawyers and teachers featured strongly. …

Getting justice

Children were asked whether they would tell someone if they were unhappy with how they were being treated. The majority said they would and parents, friends and siblings were the overwhelming choice as to who they would tell. …

Decisions made about them

Children were asked to identify what decisions had been made about them. They reported they had been made by a judge, police officer or teacher in the areas of family law, including care, criminal law and education. …

A significant majority said they had been supported through the process, and about half said that the decision had been made in a setting that was safe and comfortable. As to what would have helped, the vast majority proposed having someone that they trust present.

Almost two thirds said that they understood the decision made about them and a similar number recorded that it had been explained to them. Children were asked who they would prefer to explain this decision to them, and in response they chose family. They expressed opposition to receiving explanations indirectly such as in writing. …

When asked about the key messages for the Guidelines on Child Friendly Justice, children voted in most numbers for:

- Being treated with respect;

- Being listened to;

- Being provided with explanations in language they understand;

- Receiving information about their rights.

Key themes

A number of strong themes emerge from the analysis of the consultation with children. They can be summarised as follows:

- Family: The importance of family in the lives of children was made very clear. Every time children were given a choice as to who they wanted present, who they would confide in, who they wanted information and explanations from, children identified parents, siblings and friends as a priority.

- Mistrust of Authority and Need for Respect: By contrast, children have little faith in those in authority…

- To be listened to: children want to be heard, they want to receive information that they can understand and to be supported to participate in decisions made about them.

How the views of children have informed the Guidelines

Presentation of the findings of the consultation to the group charged with drafting the Guidelines led to the Guidelines being informed directly by the views and experiences of children. During the drafting process, numerous changes were made to ensure that the Guidelines met the needs of children…

In particular, the views of children have been used to:

- support the extent and manner in which the Guidelines recognise the right of children to be heard, to receive information about their rights, to enjoy independent representation and to participate effectively in decisions made about them. …

- ensure that adequate provision is made in the Guidelines for children to understand and receive feedback on the weight attached to their views;

- strengthen the provision in the Guidelines for the supports that children enjoy before, during and after contact with the justice system. …

Conclusion

It was vital to the effectiveness of the Guidelines on Child Friendly Justice that children were consulted about their experiences and their views. This ambitious project demonstrates the value of genuine consultation of children on issues that affect them. It illustrates how such a process can be used to strengthen children’s rights standards in the Council of Europe (and possibly elsewhere).

Assignment preparation task 6: Drafting

Building on your outline, write a rough draft of the body of your report now. Do NOT edit it yet. As you work through the rest of the module, you will work on its various parts as we discuss them. You will edit and proofread towards the end of this module.

Do not continue until you have completed this step. You will need a first draft in order to complete the activities in the next section, Writing key sections.

Keep a note of how long the drafting stage takes you and any observations about the process and record this in your Reflection File.

Progress check: Working on your first draft

You've just worked through probably the most crucial section in this module. Once you plan a coherent structure to your report, your writing task will be much easier, and you will be able to stay focused on your main message to your readers.

By now, you should have:

- selected a document to write for this module;

- completed and submitted a purpose statement and reader analysis to your tutor;

- completed and submitted an outline for your document to your tutor;

- written a first draft of the document.

If you haven't done so yet, you should return to the earlier part of the module where you were asked to submit your purpose statement and reader analysis. If you are still having trouble deciding what type of report to write or you are having difficulties with the module content up to this point discuss it with your tutor. A short exchange may be all that's needed to get off to a good start.

SECTION 2: Writing key sections

Writings are useless unless they are read, and they cannot be read unless they are readable.

Theodore Roosevelt

This section focuses on the skills required for writing specific parts of reports and proposals.

- introductions

- conclusions

- recommendations

- summaries (including executive summaries).

The examples were chosen because they clearly show the skills needed to produce the specific components. Your document may not include all of these components and may include other specific components not listed here. These four have been selected because they are common to many reports and because the skills required to write them are applicable to other types of writing too.

Identifying required components

Writers at the Council of Europe produce a huge range of reports, proposals and other documents. This course is designed to help you write any of these documents more effectively, but it cannot provide examples of every document type.

When you are assigned a writing task, it is wise to begin by asking for an excellent example of what is required. Referring to an example, whether that is a proposal crafted for the same organisation, last year’s version of an annual report or another monitoring report produced in your section can help you meet your manager’s expectations and write your report efficiently.

Analyse your example document carefully. In particular, make sure you:

- look at the report sections. Is there an executive summary? Is there an introduction?

- consider the formatting. Are the paragraphs numbered? How many levels of headings are included?

- consider the length. How long is the document overall? How long are each of the sections?

- consider the way information is presented. Are there maps, graphs, charts or other graphic elements? Is there a list of references? Are references included in footnotes or endnotes?

Adopting a style for your report

Inconsistency in style or formatting creates unnecessary distractions for the reader. When readers encounter inconsistent font styles, page layouts, numbering, graphics and so on, they may conclude there is a reason for the inconsistency and waste energy trying to find the pattern. Alternately, they may just decide that you are careless. As a writer of a document with a message to convey, it is your aim to remove these distractions in order to make your readers' job as easy as possible.

This is why it is important for you to be aware of any style guides that apply in your area of the Council of Europe. You will want to consult the guide, Style guide: Better English and style in print and online, which is included in the resources for Module 1. Be aware, though, that there are other guides in use at the Council of Europe. Be sure you find the one(s) that apply in your area.

It is particularly important to look for examples, style guides and other models if you are preparing a funding proposal. Most foundations and other funding agencies have strict guidelines that must be followed. Many provide examples on their websites or with information packages.

Assignment preparation task 7

After you have worked through the course section on each element (introduction, conclusion, etc.), work on the corresponding part of your own document. That way you will have an opportunity to apply what you are learning right away, and you will complete the assignment for the module as you complete the module.

Don't forget to reflect on the process you are undertaking by making notes in your Reflection file for each step.

If you have not completed the rough draft of your assignment yet please stop working on this section and complete your draft before you continue.

When you submit your full document at the end of this module, you should let your tutor know if you are following a predetermined style for the report and include it with your submission. That will help her or him provide appropriate critical feedback on the consistency of your report.

Writing introductions

It might be thought that a table of contents would serve the same purpose as an introduction. It does not. A table of contents is static, an introduction dynamic, and we want to be on the move towards our conclusion from the start.

When readers make time to read your document, they are likely to be squeezing this reading into a busy day filled with other tasks. They will want answers to a number of questions very quickly, such as:

- why have you written this document? What is its purpose?;

- what does it have to do with them?

- why have they received it now?

- what have you got to say?

- how are you going to say it?

In general, these questions should be answered in your introduction. If you don't supply the answers you run the risk of losing your readers' attention before they have really begun.

Although the introductory function is important in the Council of Europe documents, you will find that not all documents have a section titled Introduction. You may find sections called “preamble” or “background” that also fulfil these functions. In some cases, a report introduction will be a very basic description of the dates of a mission and those who participated. Do follow the guidance of your manager and make reference to other documents similar to the one you are writing.

In this module, we are talking about the introductions that are typically written as part of a long report for general circulation. Why do readers need introductions? The English author, C.S. Lewis explained, “I sometimes think that writing is like driving sheep down a road. If there is any gate to the left or right, the reader will certainly go through it.”

A clear introduction closes the gates, and helps the reader move smoothly through the report.

Model introduction

The best way to learn about writing introductions is to study examples.

Below is the introduction to an issue paper, “The right of people with disabilities to live independently and be included in the community”, commissioned and published by the Commissioner for Human Rights. The report’s table of contents is included after the introduction. The paper is approximately 40 pages long.

The right to live independently and to be included in the community stems from some of the most fundamental human rights standards both within the Council of Europe and United Nations systems. These standards have been captured in Article 19 of the 2006 United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). Article 19 of the CRPD also provides guidance for what is included within the concept of living independently and being included in the community.

Understanding what the right to live in the community looks like when implemented, and when violated, is an essential component for the implementation of this right by member states, as well as its pursuit by all relevant stakeholders. This Issue Paper aims to draw out the guidance contained in international standards, and in particular Article 19 of the CRPD, in order to promote this understanding. It also seeks to present this guidance to those who engage in monitoring whether and how governments are implementing the right to live in the community. Monitoring entities may include governments themselves, the international disability community, local organisations of people with disabilities and domestic, regional and international human rights’ organisations and mechanisms.

The right to live in the community applies to all people with disabilities. No matter how intensive the support needs, everyone, without exception, has the right and deserves to be included and provided with opportunities to participate in community life. Time and again it has been demonstrated that people who were deemed too disabled to benefit from community inclusion thrive in an environment where they are valued, where they partake in the everyday life of their surrounding community, where their autonomy is nurtured and where they are given choices. Programmes from around the world have shown that all types of support needs can be answered, and are better answered, in community settings, which allow for expression of individuality and closer scrutiny to prevent abuse.

The right to live in the community with choices equal to others presumes a set of options for living arrangements of which members of a community avail themselves. These vary from country to country and region to region, and their violation with regard to people with disabilities takes different forms. This Issue Paper endeavours to encompass as many of these contexts as possible. It takes into account contexts that rely heavily on institutions, as well as those that do not, that suffer from an acute lack of community support services. Though some sections may be more relevant than others when applied to a specific country, this Issue Paper aims at capturing how the right to live in the community is implemented in various national contexts.

Chapter 1 of this Issue Paper presents the basic elements of the right to live in the community. It sets out the content of the core right and how a grasp of the right (or lack of it) shapes the response.

In Chapter 2, the Issue Paper describes the roots of the right to live in the community and its evolution in European and international law.

Chapter 3 provides more detailed guidance on the implementation of the right. It also looks at the range of ways in which the right may be violated – whether by confining people to institutions, keeping them at the outskirts of society or segregating them within their own communities.

The Appendix to the Issue Paper provides a sample of indicators and guidance questions which can help assess whether, within a national context, a transition is taking place from violation to implementation of the right to live in the community.

SUMMARY

THE COMMISSIONER’S RECOMMENDATIONS

Introduction

- 1. The Right to Live in the Community: The Basics

- 1.1 The Core Right

- 1.2. How a Grasp of the Right Shapes the Response

- 1.3. Articulation of the Right: The UN Convention

- 1.3.1. General overview

- 1.3.2. Living independently

- 1.3.3. Choice, individualised support, accessibility of general services

- 1.3.4. Link with legal capacity

- 1.3.5. Beyond non-institutionalisation

- 2. International Law and Policy

- 2.1. United Nations

- 2.2. Council of Europe

- 2.3. European Union

- 3. Implementing the Right to Live in the Community

- 3.1. What Constitutes Implementation – Drawing Guidance from CRPD Article 19

- 3.1.1. Choice

- 3.1.2. Individualised support services

- 3.1.3. Inclusive community services

- 3.2. Violations of the Right to Live in the Community

- 3.2.1. Segregation in institutions

- 3.2.2. Isolation within the community

- Appendix: Indicators and Guiding Questions

- 1. Monitoring implementation

- 2. Key stakeholders

- 3. Addressing a diverse range of people with disabilities

- 4. What constitutes implementation

- 5. Violations of the right to live in the community

- 6. Moving from violation to implementation

The introduction is short and to the point. It has flow and reads as a piece of continuous text. It clusters parts of the report in a meaningful way to reveal the structure of the issue paper. Unlike a summary or an overview, it does not give the specific conclusions or recommendations. It does give a sense of what the reader can expect from the paper and directs readers’ attention to specific parts of the document.

An introduction is a contract between you and your readers. In it, you make specific commitments that must then be fulfilled. The most important of these is your statement about the purpose or focus of your report.

So, introductions in reports have two main functions; 1. to make the purpose of the report clear and 2. to explain the scope of the report.

Their lesser, but still important, functions are:

- to provide a road map to the report;

- to gain the reader's attention;

- to provide some background information;

- to indicate the authority under which the report is written (for example, who requested the report).

Your introduction should provide your readers with what they need to prepare them to understand the information in your report and act on your statement of purpose.

The functions of an introduction

Look again at the model introduction you saw earlier. This time, click on the labels indicating the functional components of an introduction to see each component in the example.

The right to live independently and to be included in the community stems from some of the most fundamental human rights standards both within the Council of Europe and United Nations systems. These standards have been captured in Article 19 of the 2006 United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). Article 19 of the CRPD also provides guidance for what is included within the concept of living independently and being included in the community.

Understanding what the right to live in the community looks like when implemented, and when violated, is an essential component for the implementation of this right by member states, as well as its pursuit by all relevant stakeholders. This Issue Paper aims to draw out the guidance contained in international standards, and in particular Article 19 of the CRPD, in order to promote this understanding. It also seeks to present this guidance to those who engage in monitoring whether and how governments are implementing the right to live in the community. Monitoring entities may include governments themselves, the international disability community, local organisations of people with disabilities and domestic, regional and international human rights’ organisations and mechanisms.

The right to live in the community applies to all people with disabilities. No matter how intensive the support needs, everyone, without exception, has the right and deserves to be included and provided with opportunities to participate in community life. Time and again it has been demonstrated that people who were deemed too disabled to benefit from community inclusion thrive in an environment where they are valued, where they partake in the everyday life of their surrounding community, where their autonomy is nurtured and where they are given choices. Programmes from around the world have shown that all types of support needs can be answered, and are better answered, in community settings, which allow for expression of individuality and closer scrutiny to prevent abuse.

The right to live in the community with choices equal to others presumes a set of options for living arrangements of which members of a community avail themselves. These vary from country to country and region to region, and their violation with regard to people with disabilities takes different forms. This Issue Paper endeavours to encompass as many of these contexts as possible. It takes into account contexts that rely heavily on institutions, as well as those that do not, that suffer from an acute lack of community support services. Though some sections may be more relevant than others when applied to a specific country, this Issue Paper aims at capturing how the right to live in the community is implemented in various national contexts.

Chapter 1 of this Issue Paper presents the basic elements of the right to live in the community. It sets out the content of the core right and how a grasp of the right (or lack of it) shapes the response.

In Chapter 2, the Issue Paper describes the roots of the right to live in the community and its evolution in European and international law.

Chapter 3 provides more detailed guidance on the implementation of the right. It also looks at the range of ways in which the right may be violated – whether by confining people to institutions, keeping them at the outskirts of society or segregating them within their own communities.

The Appendix to the Issue Paper provides a sample of indicators and guidance questions which can help assess whether, within a national context, a transition is taking place from violation to implementation of the right to live in the community.

Activity 5: The functions of an introduction

The introduction provided below is from a document entitled “Internet: case law of the European Court of Human Rights”. Read this very brief introduction and see how many functions you can identify. Copy the appropriate section into the box, then check your answers below.

INTRODUCTION

At the request of the Council of Europe Task Force on Information Society and Internet Governance, the Registry’s Research Division conducted a study on the Court’s case law in respect of issues relating to the Internet.

The aim was to provide a report for the Task Force for submission to the conference organised by the Federal Ministry for European and International Affairs of Austria and the Council of Europe on the theme “Our Internet – Our Rights, our Freedoms – Towards the Council of Europe strategy on Internet Governance 2012-2015” (Vienna, 24-25 November 2011).1

1. make the purpose clear

2. explain the scope

3. provide the reader with a framework or scaffolding on which to build their understanding

4. gain the reader's attention

5. provide background information

6. indicate the authority under which it is written (i.e. who requested it)

- 1. make the purpose clear

- 2. explain the scope

- 3. provide the reader with a framework or scaffolding on which to build their understanding

- 4. gain the reader's attention

- 5. provide background information

- 6. indicate the authority under which it is written (i.e. who requested it)

INTRODUCTION

At the request of the Council of Europe Task Force on Information Society and Internet Governance, the Registry’s Research Division conducted a study on the Court’s case law in respect of issues relating to the Internet.

The aim was to provide a report for the Task Force for submission to the conference organised by the Federal Ministry for European and International Affairs of Austria and the Council of Europe on the theme “Our Internet – Our Rights, our Freedoms – Towards the Council of Europe strategy on Internet Governance 2012-2015” (Vienna, 24-25 November 2011).1

Assignment preparation task 8: Writing introductions

Revise the introduction of your report in light of the points covered in this section and the examples given or write an introduction if you did not write one in your first draft.

In your Reflection File, record your observations about this step. Also, record the length of time it took for this step.

Writing conclusions

If the introduction sets the scene for your document, preparing the reader for what is to come, the conclusion closes the document, reminding the reader of what has been discussed. Not every type of report written at the Council of Europe includes conclusions. Issue papers usually do. Reports to parliamentary committees and reports on the application of various charters and agreements typically combine conclusions and recommendations in a single section; other reports may close with a section summarising trends and drawing conclusions. Still others, such as explanatory reports, typically don’t include a conclusion section at all. Even if the document you are working with does not require a specific conclusion the skills of conclusion writing are still valuable. Executive summaries can be improved by including conclusions and so can many other short documents that summarise longer works.

It is important to remember that in a report or proposal, the conclusion should not introduce new issues or ideas. Rather, it is a summing-up of what has gone before. It may include mention of next steps, but it does not open a new subject.

If you have the option of including a conclusion, you should. Not to do so is a missed opportunity since a conclusion gives you a final chance to reinforce the main message of your report and to revisit the main message in the light of the analysis presented in your report.

With a good conclusion, you can pull all the threads together and remind readers of the initial purpose for writing the report. In other words, the conclusion should confirm for the reader that the report's purpose has been achieved. It should also confirm that the writer/reader contract set up in the report's introduction has, in fact, been fulfilled.

Model conclusion

Let's have a look at an issue paper that includes an effective conclusion.

Following is the table of contents of an issue paper entitled Adoption and Children: A human rights perspective. This is a well-organised report, and the table of contents demonstrates the organisation of the report very well. It also gives you some idea of the main points raised. After the table of contents, you will see the conclusion. The conclusion, at two pages, is appropriately 10% of the length of the report. It consolidates the main points of the report, leaving the reader with four strongly-phrased points that are memorable and comprehensive.

Table of contents

Summary

The Commissioner’s recommendations on adoption

Introduction

- The development of adoption of children in Europe

- National adoption (adoption in the same country)

- Intercountry adoption

- The international and regional legislative framework

- Respecting children’s rights in the adoption procedure

- The “right” to a family

- The best interests of the child

- Subsidiarity

- Are potentially adoptable children not being identified?

- Children with special needs

- Necessary procedural safeguards

- Assessment of prospective adoptive parents, and matching

- Adoption by same-sex couples, or by single gay or lesbian persons individually

- Applications to adopt and the number of “adoptable children”

- Non-regulated and private adoptions

- Adoptions from non-Hague countries

- Systemic problems or isolated violations?

- Costs and contributions

- Adoption following disasters

- Conclusions

The current picture of adoption within, to and from European countries is one of very widely varying realities, but the background against which it takes place has some clear features.

Over the past 50 years, growing numbers of people have sought to meet their legitimate desire to found a family, or to take in a child who needs an alternative stable family environment, through adoption. In most cases, they have understandably been looking to adopt a very young child. To do so, people in many European countries have found it increasingly necessary to rely on opportunities to adopt a child from a country other than their own. However, the number of people seeking to adopt children considerably outweighs the number of young children who are in need of adoption and are declared adoptable. In contrast, older children and those with disabilities for whom adoption could be envisaged remain hard to place, and their numbers are far greater than those of people both willing and able to cater to their special needs.

The point has long since been reached where the wholly laudable willingness or legitimate desire to adopt a child often metamorphoses into unrealistic expectations that are expressed as effective demand for that relatively rare adoptable child. The pressures exerted, wittingly or unwittingly, because of the desire to adopt young children has led to increasingly documented instances of such children being procured for adoption by illegal means and for financial gain, particularly in the framework of intercountry adoption. Many of the systems and procedures that are in place at best do nothing to prevent these abuses and at worst may even facilitate them.

As a result, international agreements have been developed to address this changing face of adoption.

The standards and safeguards they establish are essentially directed towards ensuring four things:

- that the adoptability of children is always determined in the right way. This means not only that full investigations have been carried out on the child’s identity, background and circumstances, and all necessary free and informed consents obtained but also that transparent procedures have been strictly followed for their adoptability to be legally established. Of special concern here is the protection of the rights of birth parents, lack of support to those who only resort to giving up a child for adoption because of material poverty, and the advantage that may be taken of the vulnerability of many such parents.

- that intercountry adoption is considered and carried out for the right reasons. In practice, the subsidiarity of intercountry adoption to appropriate domestic solutions is not always respected, with few real attempts being made to find a suitable care option for children in their own country. Many countries of origin still feel under pressure to make more children available for abroad adoption. Thus, there is cause for concern, for example, when babies and toddlers are adopted from abroad from countries where alternative homes can usually be found for children of that young age. In some cases, young children are reserved for intercountry adoption by various means. They may be allowed to by-pass registration for domestic adoption or be virtually guaranteed rejection by a local adopter, for example due to fabricated medical records the existence, or exaggerating the seriousness, of an illness or disability.

- that each child is adopted by the right person(s). Professional matching of a child with adoptive parents who have the aptitude to cater to his or her specific characteristics and needs is vital. Many prospective adopters have an ideal image of the child they wish to adopt and are not adequately prepared for (or suited to) the fact that children available for intercountry adoption in many countries increasingly have some degree or form of special need. Given this developing reality, which is rapidly changing the face of intercountry adoption, it will be particularly important for the assessment of applicants to be even better tailored to determining their true willingness and ability to take on the generally more difficult task of caring for an older child or a child with disabilities since some may feel that doing so constitutes their only option for adopting. Of special concern are instances where information regarding a child’s medical or other background is falsified or deliberately withheld from the potential adopters, which can easily lead to subsequent inability to cope and rejection.

- that the adoption is carried out in the right way. Fundamental to this is that applications to adopt should be submitted and considered only in response to real needs so that prospective adoptive parents offer a home to an adoptable child rather than taking the initiative, directly or indirectly, to find such a child. Non-regulated and private adoptions, without assistance from accredited agencies and usually with minimal or no oversight by the authorities of the receiving country, must be prohibited. They are not in conformity with the Hague Convention but are still commonly taking place from non-Hague countries. They involve demonstrably greater risks of illicit practice than those carried out through accredited agencies.

These goals correspond to efforts to protect the human rights of the child, with application of the principle that the child’s best interests must be given paramount consideration in decisions to initiate adoption proceedings and in carrying them through. Determination of those interests involves thorough assessment of a wide range of factors and has to be carried out with full respect for all other rights. This process also enables the rights of birth parents to be preserved and the interests of prospective adopters to be respected.

Not only are the changes required to achieve these goals substantial, but they also cannot be brought about through the initiatives of one type of actor alone. The effectiveness of any measures to be taken by countries of origin will be jeopardised if pressures continue to be exerted by receiving countries. Unless agencies systematically refuse to operate in the framework of systems that are in clear violation of international norms, they may find themselves complicit in abuses. If prospective adopters do not receive accurate and dispassionate information on intercountry adoption needs they will not be able to adjust their plans and expectations accordingly. Thus, each actor in the process carries a particular responsibility, and all need to, and must, seek cooperation with one another to maximise the impact of their efforts.

Assignment preparation task 9: Writing conclusions

As the next step in your assignment preparation, revise the conclusion of your report, or write a conclusion if you did not include one in your first draft. Remember to ensure that it is based on discussion within the body of your report.

Record any observations you have about this step in your Reflection File, including the length of time it took.

Writing recommendations

Recommendations are often included with a report's conclusion although they serve different purposes. Whereas a conclusion offers you the opportunity to summarise or review your report's main ideas, recommendations suggest actions to be taken in response to the findings of a report.

Recommendations suggest a way forward. In this way, they become tied to the next steps that follow after the report. With background reports, occasional papers and discussion papers, recommendations are offered as potential starting points for discussion. As a result, your recommendations provide an essential focus for the readers.

In any case, your report structure should lead up to the recommendations and provide justification for them. Your report should actually grow backwards from your recommendations. Having your recommendations accepted then becomes your statement of purpose.

What makes a good recommendation?

Effective recommendations:

- are directed to an individual or group that has the power to enact them;

- describe a specific course of action to be taken to solve a particular problem;

- are written as action statements without justification;

- are stated in clear, specific language;

- should be expressed in order of importance;

- are based on the case built up in the body of the report;

- are written in parallel structure.

Do be sure to consult examples of the type of report you are writing to determine how best to present the recommendations. Resolutions can be very complex and draw on earlier resolutions and precedents. Our goal here is not to discuss recommendations at that level of complexity; rather, our intention is to focus on the basic principles of writing clear, coherent recommendations.

Sample recommendations

Review these recommendations. Although many are beyond the scope of the document you are working on for this course, they do demonstrate important components of resolutions in general.

The first example is a resolution that makes a recommendation to national governments.

The Committee of Ministers, in its composition, restricted to the representatives of the States parties to the Convention on the Elaboration of a European Pharmacopoeia (“the Convention”),

Recalling the Declaration and Action Plan adopted by the Third Summit of Heads of State and Government of the Council of Europe (Warsaw, 16-17 May 2005), Chapter III – “Building a more humane and inclusive Europe”, Article 1. “Ensuring social cohesion”, laying down in particular protection of health as a social human right and an essential condition for social cohesion and economic stability;

Recalling Resolution Res(59)23 of 16 November 1959 extending the activities of the Council of Europe in the Social and Public Health field on the basis of a Partial Agreement, and Resolutions Res(96)34 and Res(96)35 of 2 October 1996 revising the rules of the Partial Agreement;

Having regard to the decisions of the Committee of Ministers of 2 July 2008 (CM/Del/Dec(2008)1031) to dissolve the Partial Agreement in the Social and Public Health Field and to transfer activities related to cosmetics and food packaging to the European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines and HealthCare (EDQM) as of 1 January 2009, thereby rendering the EDQM responsible for developing harmonised approaches to ensure product quality and safety in the areas of cosmetic products and packaging materials for food and pharmaceutical products;

Having regard to the terms of reference of the Consumer Health Protection Committee (Partial Agreement) (CD-P-SC), as approved by the Committee of Ministers on 11 March 2009 (CM/Del/Dec(2009)1050) and renewed on 21 September 2011 (CM/Del/Dec(2011)1121);

Considering the efforts made over several years (under the former Council of Europe Partial Agreement in the Social and Public Health Field) to harmonise national provisions in the public health field and, in particular, in the sector of food contact materials;

Considering the health risk posed to humans by metals and alloys that are used in food contact materials and articles because of the release of metal ions into foodstuffs;

Taking into account Regulation (EC) No. 1935/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 October 2004 on materials and articles intended to come into contact with food, Regulation (EC) No. 2023/2006 on good manufacturing practice for materials and articles intended to come into contact with food and Regulation (EC) No. 852/2004 on the hygiene of foodstuffs, which although not binding for all of the States Parties to the Convention, should nevertheless be applied by all;

Taking into account that the Guidelines on Metals and Alloys first published by the Council of Europe on 3 February 2001 and revised on 13 February 2002 have provided useful information and support to professionals in the food contact material industry, national authorities and other stakeholders that are involved in ensuring compliance with the provisions of the aforementioned Regulation (EC) No. 1935/2004 and in particular, its general requirements laid down in Article 3 (1);

Considering that, in the absence of specific requirements at the European level for metals and alloys used in food contact materials and articles, a Technical Guide has been produced by the Committee of Experts on Packaging Materials for Food and Pharmaceutical Products (P-SC-EMB) that supersedes the aforementioned guidelines;

Taking note that this Technical Guide will be regularly updated by the P-SC-EMB and approved by the Consumer Health Protection Committee (CD-P-SC, Steering Committee under the responsibility of the Committee of Ministers) and published under the aegis of the European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines and HealthCare (EDQM);

Being of the opinion that each member State, faced with the need for provisions in this field, will benefit from harmonised provisions at the European level,

Recommends to the governments of member States Parties to the Convention that they adopt legislative and other measures aimed at reducing the health risks arising from consumer exposure to certain metal ions released into food from the contact with metals and alloys during manufacture, storage, distribution and use according to the principles and guidelines set out in the Technical Guide on Metals and Alloys used in food contact materials and articles. These recommendations shall not prevent governments from maintaining or adopting national measures that implement stricter rules and regulations.

Resolution CM/Res(2013)9 on metals and alloys used in food contact materials and articles

(Adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 11 June 2013 t the 1173rd meeting of the Ministers’ Deputies)

The second example comes from the report of a group of specialists on the promotion of gender mainstreaming. These are more informal recommendations, growing out of the report the specialists wrote.

The group recommended that the [organisation name] should continue their work on this issue, develop strategies for the integration of gender mainstreaming at school, and that:

- Models should be developed for assessing policies, practices and results of implementing mainstreaming;

- A code of ethics for teachers, head teachers and supervisor teams should be drafted;

- A database inventorying the different teaching resources existing in Europe for implementing gender mainstreaming should be developed;

- A manual of good practice in gender mainstreaming in schools in Europe should be developed;

- A comparative study of gender mainstreaming practice in schools in Council of Europe member States should be drafted.

Activity 6: Improving recommendations

Read through the recommendations below. Each of the recommendations contains at least one flaw. Identify the flaw, and rewrite the recommendation. You should base your comments and revisions on the writing effective recommendations principles on the previous page.

Example 1:

Interactive networks for exchanging good practice at European level should be set up.

Rewrite the recommendation

The recommendation is not directed at any group or individual. The description is not specific.

The [organisation] should create, publicise and maintain an interactive database of European best practices.

Example 2:

Because there have been so many failures in the implementation of this practice, we recommend that [organisation] introduce a more rigorous monitoring process and system of reports.

Rewrite the recommendation

The justification provided (because there have been many failures) is inappropriate and vague.

We recommend that [organisation] introduce a more rigorous monitoring process and system of reports.

Example 3:

To allow substantive issues to be covered, papers should be provided in advance, with an agenda, so that participants have time to prepare and have a more productive discussion.

Rewrite the recommendation

The recommendation is not directed at any group or individual. Given the variety of suggestions, it may be that several different individuals would need to be involved. None of the suggestions are specific.

Conference organisers should distribute both the agenda and papers for prereading at least 30 days in advance of the meeting. Conference participants should be required to submit their papers for review at least 60 days in advance.

Assignment preparation task 10: Writing recommendations

If your report lends itself to having recommendations review them now. If you can improve them in the light of the points covered in this section and the examples given.

Record any observations you have about this step in your Reflection File . Also, record the length of time it took for this step.

Writing summaries

The ability to capture your main points in summary form is the key to getting your message across and achieving your desired response from your reader. A well-written summary will encourage readers to tackle your document or, at a minimum, to find details within it relevant to their needs. A poor summary will minimise your chances of having your work read.

You should consider including summaries wherever possible even for short reports and even if it is not mandatory. A well-written summary prepares your reader for the detail of your report and increases your chances of at least getting across your main ideas if the report is just skimmed. Interestingly, the increased use of the Internet for posting reports is also increasing the use of summaries as many reports are being introduced with a summary on a webpage. In a case like this, it is critical that your summary provides a brief but comprehensive rendering of the report.

Other terms similar to summary that you may come across in your report writing work include:

- Introduction

An introduction usually relates the topic under discussion to a wider field and gives the necessary background information. As you now know, it should clearly state the purpose of the report and give its scope. It should also explain the arrangement or structure of the report in order to give the reader a roadmap or framework with which to read the report. It does not summarise conclusions or recommendations. - Abstract

An abstract specifically refers to a summary of scholarly or academic texts. - Synopsis or outline

These are more detailed than an abstract; both retaining the point-by-point ordering of the original. They may be drawn up by either the original author(s) or by someone else (for example, a speechwriter working from the original document).

Summaries and executive summaries

Summaries and executive summaries serve the same purpose: they provide a brief version of a longer report. An executive summary, as the name suggests, targets a reader who makes funding, personnel or policy decisions and needs information quickly and efficiently. Summaries should be informative and not only descriptive. That is, they should both describe the scope of the report and present what is in it. For example, an executive summary should include the recommendations, not just say ”Six recommendations were made”.

These guidelines should help you create effective summaries regardless of the size of the task. Summaries must:

- be placed at the beginning of the report, after the table of contents but before the introduction.

- be written in well-constructed paragraphs that flow logically from one to the next;

- follow an introduction-body-conclusion structure and be self-contained;

- discuss purpose, findings, conclusions and especially recommendations;

- include only essential or the most significant information;

- not add new material;

- not assume complete background knowledge in the reader;

- use simple and concise language;

- be less than five per cent of the original document and preferably less than one page for short reports;

- be placed at the beginning of the report, after the table of contents but before the introduction.

Evaluating a summary

In this example, you will look at a table of contents and summary, then evaluate the effectiveness of the summary.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Executive summary

- Introduction

- Applicability of the European Convention on Human Rights

- Mission programme

- Right to return

- Rights of displaced persons to care and support

- Right to be protected against the danger from explosive remnants of warfare

- Right to protection against lawlessness and intercommunity violence: Right of detainees and persons in hiding to receive protection

- International presence and monitoring for the protection of human rights and addressing impunity

- Conclusions

Displaced persons in XXXX and XXX

Executive summary