Introduction

This module will guide you through an analysis of your work-based writing strengths and weaknesses. On the basis of your analysis, you will be able to fine-tune your approach to readers and to writing.

At the Council of Europe, mastery of the writing process is essential. The demands are great and the goals important. Writing plays a vital role in the Organisation’s goals: to reinforce democracy, human rights and the rule of law and to develop common responses to political, social, cultural and legal challenges in its member states. Without writing, there would be no accurate recording of actions taken or discussions among governments and others, and no means of informing people of successes achieved and challenges ahead.

The writing context is challenging. Documents must be prepared rapidly, and they must be presented in both French and English. Writing is done at multiple levels of complexity, from the legal judgments prepared in the Court to briefs prepared for members of the Parliamentary Assembly to newsletters, Facebook updates and other more casual writing intended to inform the public of multiple nations. These constraints have an effect on the format and style of the writing required.

This course aims to help you handle work-based writing tasks as effectively as possible. It seeks to help you establish strategies and skills that are general enough to fit a wide range of writing tasks. Ultimately it aims to assist your busy readers by making their reading tasks easier through writing that is clear, well organised and as brief as practicable.

Module objectives

By the time you have completed this module, you should be able to produce work-based writing that shows you can:

- formulate a clear objective for each document you write;

- analyse your target readers and their needs and write appropriately to meet those needs while achieving your own objectives;

- identify barriers that may prevent written communication from being effective;

- write in a style that is appropriate to your readers and your work context;

- develop strategies to help improve your writing process;

- recognise aspects of ineffective writing;

- apply editing techniques to help avoid and correct ineffective writing.

You will find activities throughout this course. As you work your way through the first module, you will use the activities to analyse your own writing and try some new approaches. The activities will help you focus on the strengths and weaknesses of your own work. You will be able to try out some analysis of your own work as part of the Module 1 assignment.

The work in Module 1 lays the foundation for the second level modules. You will choose and complete one of these second level modules in order to complete the requirements for passing this course.

You will find at least some of the concepts in this module very familiar. If you are tempted to skip any exercise because you feel you already understand the principles and practices in it, please make sure you at least think about the concept in relation to your own writing. There is often a gap between what we understand and what we put into practice. Many of the activities are actually harder to do than they look. Try them before you compare your responses with the suggested responses. Otherwise, you will miss the benefits of practice with immediate feedback that this course offers.

Communicating with your tutor

You should have made contact with your tutor by now. Your tutor is there to help, motivate and provide an active resource for you. Contact your tutor whenever you need further explanation of the course materials or clarification about what to do.

You will contact your tutor through Moodle. Moodle allows for both individual, individual-to-individual e-mail and individual-to-group discussion boards. Your tutor will let you know the best way to be in touch.

As you work through the module, you will see various points labelled “Progress Check". These indicate good times to contact your tutor if you have any questions or comments about the course materials or if you want to send all or part of your assignment work for review. These reminders are not mandatory assignments, they are a benefit for you. Regular contact with your tutor will help you get the most out of the course.

Assignment preparation task 1: Thinking about your assignment

Your assignment for this module consists of two separate parts: Assignment 1A and Assignment 1B. Each of these parts is explained in detail at the end of the module. As you work through the module you will be given guidelines for preparing your assignment. This page offers some advice for thinking about your assignments.

Assignment 1A involves a critical analysis of your own workplace writing; Assignment 1B involves creating a portfolio of examples of specific points from your own writing. In preparation for these assignments, look back through some of the writing you have been doing lately at work and choose three or four samples. These can be in any format: letter, memo, fax, e-mail (of some length), briefing note, report, etc. A variety would be most useful. Either print them or put them in a folder on your computer desktop so that you can refer to them easily when you need to as you begin to prepare the assignments for the first module. You will choose one of these samples to analyse in Assignment 1A and draw on them to find examples for the portfolio you will create for Assignment 1B.

A note for lawyers: when you select your workplace writing examples, it is likely best to exclude judgments that you have written. The writing of judgments, in particular discussion of the application of case law, is highly specialised and beyond the scope of this course. It is appropriate to consider some sections of judgments; for example, descriptions of the circumstance of the case can make a useful example of your writing.

Progress check: Your first assignment

At this point, you are only beginning to think about the assignments. However, if you are uncertain about what to do it is a good idea to contact your tutor to confirm that you are on the right track.

SECTION 1: Thinking about communication

Genius is the ability to put into effect what is on your mind.

F. Scott Fitzgerald

To be an effective writer, you need to understand how communication works and what prevents it from working. Understanding the theory will give you the tools to:

- analyse workplace communication situations and choose the best approach for each writing task;

- predict and prepare for barriers that could prevent you from getting your readers to do what you want.

Barriers to communication

There are many things that can interfere with clear communication. We think of these things as barriers – situations or differences in understanding that can come between you and your reader, making it difficult for them to understand what you are telling them or to act on your purpose. When you recognise that potential barriers exist, you have taken the first step to avoiding them.

Potential barriers to clear communication

- Emotional (hostility, indifference on the part of the reader, other pressures on the reader, etc.) Examples: your reader is distracted by an impending deadline for a report they are writing; your reader has recently received criticism from someone in your department for their work on another project.

- Semantic blocks (connotations of words, discriminatory language, etc.) Examples: your reader finds a word you used to describe people over 60 offensive; your reader interprets the word “illiterate” as an insult to those it describes and prefers another term.

- Physical barriers (what your eyes see on the page or the screen) Examples: your reader is reading a complex document on their mobile phone; the photocopy you distributed at the meeting is very faint.

- Timing barriers Examples: your e-mail requesting a favour arrives late in the afternoon on the Friday before a long weekend; you have requested information that is not yet available.

- Perceptual (seeing what you expect to see, the reader's own experience, etc.) Examples: you are writing a report on something in which your supervisor is an expert, and your conclusions are slightly different from your supervisor’s conclusions; your data show that a situation has changed after a long period in which it remained the same; your reader expects no changes so reads with little attention.

Activity 1: Identifying barriers

Consider the following scenario, with these questions in mind:

- What barriers can you predict?

- How would the environment influence the wording and timing of your memo to your supervisor?

You would like to get approval for a budget increase for your project. The project is going well and you feel your request is justified. However, you know your immediate supervisor has been under pressure lately, particularly regarding financing of other projects undertaken by your section. You will be leaving in two weeks for an extended trip, and you hope to get this issue resolved before then.

What barriers can you predict?

- Emotional – the supervisor has recently been under pressure due to the financing of other projects.

- Timing – since you’re going on leave, you may feel stressed about seeking resolution. This could have an impact on your town.

How would the environment influence the wording and timing of your memo to your supervisor?

- Emotional – provide evidence to support your claim that the project is on track and the request is justified. Structure your request to demonstrate the benefits to the department.

- Timing – if possible, be flexible; your supervisor may appreciate the opportunity to reflect on the budget issue while you are away. If that is not possible, try to make sure you get the request to the supervisor early in the two-week period, make yourself available for follow-up discussions and make sure the reader knows the timeline right away.

Assignment preparation task 2: Identifying barriers

During the coming week, identify and note examples of barriers that might hinder you from getting your written messages across effectively. Note the steps you took to minimise the effect of the barriers you anticipated. This data will be useful when you come to writing your assignment.

Here are some examples of the kind of barriers you might find.

- Your new supervisor reads books about grammar and punctuation for fun. You don’t worry too much about proofreading e-mails. (Mistakes in your e-mail could raise a perceptual barrier, if the supervisor sees your work as unprofessional.)

- Your reader has only worked for the Council of Europe for three weeks. (This could lead to a selectivity barrier; your reader may be overwhelmed by all the e-mails and requests they are receiving in the new position. It could lead to a timing barrier if you have sent an urgent request; your reader may not feel they have enough information to respond quickly.)

Desired response and purpose

Defining your statement of purpose

When you write at work, you write to inform, persuade, publicise, convince, record and so on: to make a difference to what your readers know. To do this successfully, you must know both the subject and what you want to achieve: your statement of purpose.

Determining the desired response you want from the reader

Good work-based writing is outcome-oriented. In other words, effective writing is very clear about what writers want readers to do as a result of reading their documents. Keeping this concept constantly in mind helps you in two important ways. First, you no longer waste time writing things that neither further your purpose nor meet your readers' needs. Second, you write more clearly. Writing without a clear objective is a sure path to ineffective writing that it is both boring to produce and read.

Pinning down your purpose

When you become outcome-oriented in your writing, you produce documents that are more effective and more interesting. As a first step, you must work out what you actually want your reader to do. Writing a purpose statement can help you stay focused on your purpose.

As a result of reading my message (report, article, e-mail), my reader will …

Examples

- As a result of reading my letter, my supervisor will arrange for training for the department.

- As a result of reading my e-mail, my colleague will meet me at the airport.

- As a result of reading my report, the department will change its policy.

Once you have identified the kind of response you want, you will find it easier to phrase your minutes, letter, report or proposal to get what you want the first time. As you work your way through the production of your document, your statement of purpose gives you a constant point of reference. It keeps you on track and helps you produce brief, reader-focused writing.

Activity 2: Statement of purpose

In this activity, you will need to consider statement of purposes for the following forms of communication. Write the objective in the space below the description of the message.

- A poster advertising this course.

- An e-mail to colleagues requesting assistance with planning for an upcoming professional development session.

Your Objective

As a result of reading this poster, Council of Europe staff will enrol in the course.

Your Objective

As a result of reading my e-mail, my colleagues will offer to assist with planning for the professional development session.

Assignment preparation task 3: Analysing barriers to communication

In the previous assignment preparation task, you were asked collect samples of your writing. Take one of those samples now and think about the quality of communication you achieved.

As you review your selected writing sample, consider the following questions.

- What was your purpose?

- Who was the audience and what were the audience’s needs?

- Were you aware of any potential barriers to communication?

- Did you take actions to overcome the barriers?

- Did the document achieve your purpose? If not, why not and what might you do differently next time?

As you write about this experience, save your work in a Word document. You will be able to use this analysis as part of your Assignment 1A.

Analysing your readers

When you write, you have a purpose you want to achieve. You may be making a request, persuading your reader to change their mind or making a recommendation for action. To achieve your purpose, you need to focus on your readers’ needs (not on your own) during every step of the writing process. When you pay attention to your readers’ experiences and expectations, you increase your chances of inspiring them to the action you want to see.

When you are writing internal documents, you may be in the fortunate position of knowing quite a lot about your readers. Other times, though, you may know very little about them, particularly if you are writing for an audience external to the Council of Europe. In these circumstances your task becomes more difficult, and you will need to be careful not to assume background knowledge that the reader may not have. Avoiding jargon is especially important.

Keeping the reader uppermost in your mind as you write is the single most important way to improve your writing.

Identifying and classifying your reader

It is most likely that you will have multiple readers for your writing, some primary (like your immediate supervisor) and others more remote (secondary) but who, nevertheless, are important to the achievement of your purpose. It is useful to identify the key decision-maker among your readers. Who can authorise the action you want taken?

- For someone taking minutes of a meeting, this may be the chairperson who signs off on the minutes.

- For someone writing an audit report, this will be the person or persons who have the power to implement the recommendations.

Writing is more difficult if you have both primary and secondary readers and even more difficult if you don't have a clear idea of your readers’ knowledge and understanding of what you are writing about. Nevertheless, you can make some assumptions based on what you know of the readers’ roles. Most busy professionals, for example, do not have time to read overly long documents.

Characteristics of your reader

When thinking about your reader, consider:

- your reader's familiarity with the subject matter;

- your credibility with your reader;

- beliefs or values that may prevent your reader accepting and acting on your document;

- time, budgetary, psychological or other pressures upon your reader;

- reading format of your document: screen or paper.

Good writers always keep their readers in mind. They remember their readers because they want their writing to achieve its purpose and they target the readers who can make this happen.

Assignment preparation task 4: Analysing your reader

Assignment 1A requires you to analyse something you have written in the past. Who were the readers of this piece of writing? Was it one person? Several? What do you know about the readers of this writing sample? What was your desired response from them?

The purpose of reader analysis is to help you focus on your reader's needs. In this module, you will use reader analysis to think about something you have already written. In the next module, whether you are writing a long or a short document, you will use reader analysis as part of the planning process.

Once you have internalised the concept of reader analysis and then begin thinking habitually in a reader-oriented way, you will likely find you don’t need to use a form. The form can be helpful, though, especially as a basis for collaborative writing.

Click here to open the Reader Analysis Form. Save a copy to use for your first assignment.

SECTION 2: Adopting a writing strategy

The desire to write grows with writing.

Desiderius Erasmus

In this section we'll work through an approach to write efficiently. You should find this approach applicable to all work-related writing tasks regardless of the format (report, briefing note, e-mail, etc.).

Effective writers often write their first drafts without worrying about mistakes in spelling, grammar, punctuation or sentence and paragraph structure. They stay focused on getting down what they really want to say. Then they go back and look at how to say it correctly.

A workable procedure is as follows:

- prewriting

- organising

- drafting

- editing

- proofreading.

In this section, you'll work through these five steps.

Step 1: Prewriting

Prewriting is about generating material or ideas or both. Whether writing down the information you have inside your head or researching outside sources, you have to start somewhere. Many of us, confronted with a daunting writing task, will suffer from what is known as writer's block. Prewriting techniques can help you overcome this by getting something onto the page or screen quickly.

Prewriting techniques

The following techniques explore methods you can use to help you produce a first draft quickly, avoid writer’s block and clarify your thoughts. Try some or all of these early on in the writing.

Brainstorming

Write down all the ideas you have about your writing task. You can do this on paper or directly onto your computer. If you prefer to speak while you’re brainstorming, you can even record brainstorming ideas on your voice mail or with another digital recorder.

While brainstorming:

- do not cross out or delete any ideas or words;

- do not worry about spelling or finding the correct words;

- do not allow anything to interrupt your flow of thought;

- do not evaluate or criticise any aspect of your writing.

The following techniques are really variations on the theme of brainstorming.

The random list

List everything that comes to mind and then sort it into groups. Look for connections: sequential, spatial, chronological, topical, pros and cons, etc.

FCR

This technique is useful if you will be required to make recommendations. Divide your page into three headings: findings (F), conclusions(C) and recommendations (R). List your ideas under one of these three categories.

Journalistic approach

Useful if your task is to convey information. Ask and answer six questions:

- Who?

- What?

- When?

- Where?

- Why?

- How?

Question and answer chain

Look at the subject from your readers' perspective. Put yourself in your readers' position by asking:

- What are my readers' main questions likely to be?

- What do they need to know?

Examine your answers to these questions. What additional questions emerge? Follow the question and answer chain until you have exhausted all questions.

Free writing

Set yourself a limited time for free writing: say five minutes for a task like writing a letter. Write down everything you can think of to include in the letter without worrying about grammar, spelling, sentences, structure or anything else. If you get stuck, repeat the last words you have written until new thoughts start to come.

Whichever brainstorming approach you take, the end result will be similar. Instead of a blank piece of paper, you will now have a list or several paragraphs containing many of the ideas you want to include in the document you are writing.

Outlining your ideas

The Outline facility (under the View menu) in Microsoft Word is an efficient tool for brainstorming. You can use the Outline facility to:

- build your plan;

- reorder information;

- change headings;

- add to or delete from the plan at any stage.

One of its advantages is that whatever work you do in the Outline view will immediately appear in your document; you are not wasting any effort at all. Outline lets you work in any part of the document in any order you choose.

Step 2: Organising

From thinking to writing

Once you have come up with some ideas or gathered your information in whatever way is comfortable for you, you must bring some order to them and some structure to your document. The process of generating ideas is quite different from the process of structuring them.

Keep in mind that your reader doesn't really care about the process you went through to get to your conclusions or recommendations. The reader wants a clear, concise end product, together with enough proof to show that you had adequate information to base it on, and that your thought processes were logical. Organising your document often means deciding not to include some of the ideas you brainstormed in the prewriting step.

Developing a hierarchy of ideas

Effective structure or organisation is based on providing a hierarchy of ideas for your reader. You, as the writer, have to do the hard work so your reader doesn’t have to. If you don't, the reader will give up on your document.

To provide a clear hierarchy, you need to:

- focus on your statement of purpose;

- write a topic sentence that conveys the main message you want the reader to get;

- stress your conclusions and recommendations;

- divide your writing into main ideas;

- subdivide these into supporting ideas.

Next you need to choose an appropriate order for your ideas. This order will depend on your purpose – your statement of purpose.

When your objective is to explain something, you can order by means such as:

- time

- components

- level of importance.

The reader needs some kind of framework in order to follow your explanation. When your objective is to ask for action you can use:

- a direct approach for a reader you think is likely to agree with you;

- an indirect approach for a reader you think will disagree with you.

Activity 3: Organising

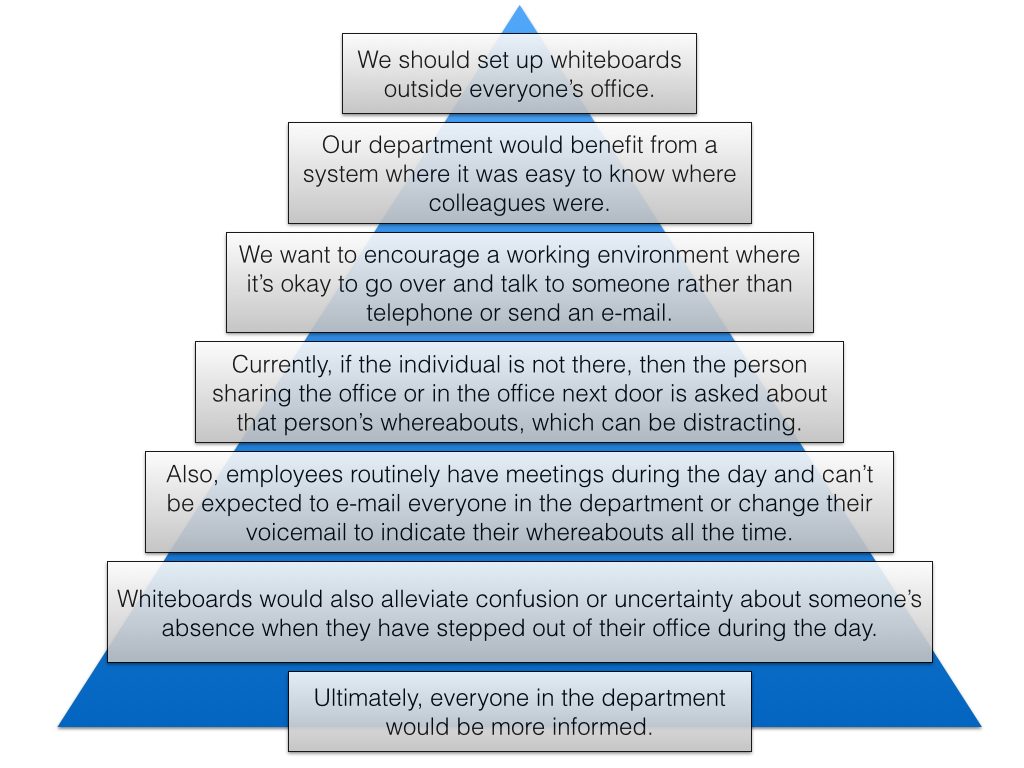

Let’s say you are interested in introducing a new practice in your department: putting up whiteboards outside all offices for everyone to indicate their presence or absence. This is bound to be acceptable to some but not to others, for various reasons. For example, you might think this is a good way to let people know where you are when you’ve stepped out of the office. However, others might see the whiteboards as a way of keeping track of people’s movements or instituting an unwelcome level of control over staff members.

Now suppose you wish to suggest this idea to your supervisor in an e-mail. If you knew your supervisor were already interested in this idea or had complained about not knowing where people were when they were out of the office, then you have some context to guide the organisation of your ideas. You could begin simply by stating your main point.

The following diagram indicates a / approach to this type of e-mail: (Click the correct choice.)

Now consider that you were writing the same e-mail to someone who might be more hostile to the idea. The following diagram indicates a / approach to this type of e-mail:

You will read more about this type of arrangement of ideas when you come to the section on paragraphing in this module.

You should be aware that the indirect approach, while useful in some circumstances, is rarely used in professional communication. In most cases documents are written in a direct style.

Step 3: Drafting

Drafting refers to the actual process of putting the first version of the document together. Four useful hints for successful drafting are:

- Concentrate on getting down what you want to say. Free up the writing stage by ignoring both mechanical errors (spelling, grammar, punctuation, etc.) and the search for the perfect word. Just keep your thought flow going.

- Do not feel you must write an introduction first or stick to a beginning-to-end structure unless that is what works best for you.

- If you work best on paper, print a copy with plenty of space available: triple spaced and with wide margins.

- Leave a time gap between drafting and editing.

Sometimes you won't have the luxury of time for a thorough drafting process. You may think that you just need to get down to writing a polished version and forget about the drafting. Really, though, time spent in drafting will save you time in the final writing process. Many people find that it is quicker to write a rough draft and polish it than it is to write a finished draft in one attempt. Drafting time is worth it!

Step 4: Editing

Careful editing is key to effective writing. It should not be done immediately after drafting. A time gap, even a short one, will enable you to look at your writing with the eyes of the reader rather than the writer.

Editing is a two-stage process: macro- and micro-editing.

Macro-editing

Editing at the macro-level involves looking at the big questions:

- How well will the document achieve your purpose?

- How well does the document convey your main message to your reader?

- How coherent is your document?

- How appropriate is the document for readers and how effectively has it met their needs?

- Is the overall shape, look and design of the document appropriate for your objective?

When you read a document at the macro-level, identify anything that will be counter-productive to achieving your purpose. By considering your reader(s), you may decide that you need to:

- add information if they need more context or background to your message;

- eliminate extra information if they are very familiar with your subject;

- add examples to clarify your points.

By focusing on the overall structure of the document, you may decide that your message will be clearer if you:

- reorganise the document;

- strengthen particular sections of your document, like introductions and recommendations;

- clarify the connections between components, like findings, conclusions and recommendations;

- improve the transitions between sections and between paragraphs.

Micro-editing

Editing at the micro-level is about making sure all the mechanical elements are correct, such as:

- sentence and paragraph structure

- grammar

- punctuation

- spelling

- word usage.

These elements are important since mistakes can damage your credibility or can distract your reader from focusing on your message. At worst, they can brand your effort as unreliable or make it impossible for the reader to understand your message.

Micro-editing is something you should be doing as you edit your documents. You will have another chance to catch these errors when you do your proofreading as well. Although this course assumes a good level of prior competence in mechanical elements, your tutor will give you feedback on any consistent problems identified in your work and will refer you to resources for further help if necessary.

Many people in the Council of Europe are working in a language other than their mother tongues. When speakers and writers of English as an additional language write in English, errors influenced by their first language may be present. In general, though, this type of error is different from the more avoidable mechanical errors we are discussing here.

Step 5: Proofreading

Proofreading is the final check of your document to ensure that it is error free. This checking is your responsibility because you are the owner of the document. (Other resources in the Organisation, such as the language checkers who work at the Court, may be available to you. Begin with the idea that the responsibility is yours, however.) It should never be neglected. Even quick e-mails need careful proofreading before you press that 'send' button.

If you try to proofread a document in the same way as you normally read, you will likely miss errors. In normal reading, we predict what the text is going to say and then confirm our predictions by sampling some of the text. We don't actually read every word. This problem is compounded by familiarity with the text. We know what we meant to say and with a quick read we mentally fill in the meaning as we go. Good readers more often than not make poor proofreaders because they are so focused on extracting meaning rather than on the surface structure of what they are reading.

Proofreading tips

To proofread effectively, you need to move away from your normal way of reading. Below are some of the techniques used by professional proofreaders:

- Read the document aloud. This helps you to focus on every word.

- Use a piece of paper to reveal only one line at a time. This prevents your eye from doing its normal sampling and predicting movements.

- Go through the document several times, each time focusing on a different aspect (for example, once for repetition and omissions; once for spelling and punctuation; once for layout).

- For really important work, get a colleague to proofread your document or find out what other resources are available in your department. (Writers are usually too close to their documents to proofread well.)

- Allow enough time for proofreading and always leave an interval between finishing the writing and doing the proofreading.

- Use the spell and grammar checker, but remember that it will not pick up all errors. See the section on Using Electronic Tools to learn what your spell checker can and cannot do.

Activity 4: Proofreading

The task

Proofread the following to identify any errors.

Example 1:

Paris

in the

the spring

is so beautiful.

It is easy to miss small words when you assume you know what you are reading.

The word “the” is repeated.

Example 2:

It is hoped that this law will reduce the incidents of exploitation of legal minors.

Words which sound alike can be easy to misspell, and can easily be missed when proofreading.

It is hoped that this law will reduce the incidence of exploitation of legal minors.

Example 3:

The joint guidelines will published in several languages and disseminated by the Office, with social dialogue activities and training to encourage their implementation.

It is easy to skip over verbs; our minds quickly fill in words that are needed.

The joint guidelines will be published in several languages and disseminated by the Office, with social dialogue activities and training to encourage their implementation.

Using grammar and spell checkers

Do not rely solely on electronic writing tools. You still need to read your work very carefully with your own eyes. With electronic writing tools, you must be the one in charge. You should dictate to the software what you want checked. To make these tools work efficiently for you, you need to have a good idea of the strengths and weaknesses of your own writing style.

Using the grammar checker

To use the grammar checker effectively, you need to have a reasonable understanding of grammatical terms. Here are some that the grammar checker identifies:

- Passive sentences In passive sentences, the subject of the sentence has the action performed on it. Although the passive tense can be useful, too many passive constructions make your document boring to read.

- Phrases These are simply groups of words without verbs (for example, of the Government).

- Possessives If you have difficulty knowing where to place an apostrophe you need to have this box checked. Possessives are words that show ownership (for example, The Director's staff). The misuse of “it's” and “its” is a common problem.

- Relative clauses These are clauses that begin with words like who, which and that. Word concentrates on using the correct pronoun and on punctuation and placement.

Using the spell checker

The spell checker in Word is a powerful and highly useful tool. It enables you to write quickly without undue concern for spelling errors and it will pick up typos for you. However, you should be aware of what your spell checker cannot do.

Your spell checker cannot:

- replace the need for final proofreading;

- distinguish between easily confused words like principle and principal (your grammar checker can, if you click on COMMONLY CONFUSED WORDS in the customising option);

- pick up an incorrect but real word that you might have accidentally typed in (for example, “the Director new the informant”);

- recognise proper nouns; it will pick them all up unless you add them to the custom dictionary (for example, Jijiga).

Similarly, you cannot rely entirely on the autocorrect feature of your tablet or other mobile device. Watch carefully for auto-correct suggestions, particularly for names and other proper nouns. Unnoticed changes can cause embarrassment and misunderstanding and can look very unprofessional.

Activity 5: Proofreading vs. spell checker

Look at the following sentence.

The growing importence of Information and Communication Technologies a cross the world is changing hour lifestyle, and has bean at the centre of concussions, both four socio-economic research and police-making, fore over two decades.

Copy and paste this sentence into an MS Word document and then run a spell check. The spell checker may find just one error. You will have noticed there are more problems than that!

The growing importance of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) across the world is changing our lifestyle, and has been at the centre of discussions, both for socio-economic research and policy-making, for over two decades.

Assignment preparation task 5: Describing your writing process

Make some notes on what you have discovered about your practice of the writing process as described in this module. You will need this data for Assignment 1A.

You can include the ideas from these notes in your analysis of the selected piece of writing that you are providing as part of Assignment 1A. In your analysis of this writing sample, consider the following:

- What was the process you followed for the writing sample you are providing?

- Did you organise your writing?

- Did you write a draft before you prepared a final version?

- Did you do any editing and proofreading before completing your writing sample?

- What effect did any of these steps in the process, whether you did them or not, have on your final product?

Progress check: Writing strategies

You are at about the halfway point of the first module. How's it going? This is a good time to let your tutor know about your progress.

Some questions to consider are:

- Have you managed to find a suitable writing sample to analyse for the first part of your Module 1 assignment (1A)?

- Are you finding the content of this first module relevant to your needs as a writer at the Council of Europe?

- How are you finding the material: difficult, easy, confusing, clear?

SECTION 3: Developing your writing skills

A small daily task, if it be really daily, will beat the labours of a spasmodic Hercules.

Anthony Trollope, English author

Thinking and writing processes differ. Thinking can be loose and unstructured. The pre-writing process, and the writing of a first draft, mirrors this. However, if writing is to be effective the final product must be coherent so that the reader can follow the logic of the document.

Coherence is achieved by:

- putting ideas together in your sentences in a way that shows the relationship between the ideas;

- placing sentences in paragraphs in a way that all sentences contribute to the paragraph's central idea or theme;

- ensuring that document components are linked together logically;

- using the logic of your organisation to hold together paragraphs and enable an easy flow from one paragraph to the next.

Without these features, your writing will lack coherence (flow), and your reader will have a difficult time understanding you. There are many factors in writing that work together to create a coherent and convincing document. In this section, we will explore some of the areas where flow is most frequently lost. We will think about coherence in specific document types in the second modules.

Putting ideas together

Sentences are made up of ideas. At its most simple level, a sentence can have just one idea, for example:

Reading such a sentence, the reader probably expects to know why the request cannot be granted. This is a related idea that may be placed in the same sentence.

In this example, the connection between the two ideas is quite obvious. It may be as effective to convey this idea in two sentences:

However, this does leave out the relationship between the two ideas and forces readers to work it out for themselves. In a straightforward example like this, that’s fine. When the situation is more complicated, a good sentence shows the relationship between the parts clearly by using the correct joining words. On the other hand, if a sentence uses the wrong joining word, it can change the entire meaning of the sentence or cause great confusion.

Joining ideas of equal importance

If a sentence has two ideas of equal importance closely enough related to be in the same sentence you need a joining or coordinating word (also known as a coordinate conjunction) that will keep them equal. Note that it is never correct to use a comma to join two sentences.

Below is a list of coordinating words. Click on each word to see an example of it in a sentence.

| Coordinating word | Example |

|---|---|

| and | I take the minutes and circulate them to those who attended. |

| but | Some progress has been made, but there is still a lot to do. |

| so | The deadline was important, so I worked long hours to finish the project. |

| nor | We cannot support this plan, nor can we encourage others to do so. |

| semi-colon (;) | We cannot grant your request; we have no funds left in this year’s budget for this kind of expenditure. |

Joining a main idea and a subordinate idea

Often when we want to indicate the relationship between two things in a single sentence, we want to make one component the main idea and join it to a related but subordinate or less important idea. For this job, you need different joining or subordinating words. Below is a list of some of these words divided into different categories.

| Category | Coordinating word | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Time | when | We will discuss this further WHEN more is known. |

| before | BEFORE she can return to work, they must make arrangements for childcare. | |

| as | I try to be brief AS I write my e-mails. | |

| Conditional | if | IF it is my turn to take minutes I am glad to do it. |

| as long as | I will attend the meeting AS LONG AS you also plan to go. | |

| unless | It will be difficult to complete this task UNLESS we all work together. | |

| Cause and effect | because | BECAUSE I have a keen eye for detail, I find many mistakes when I proofread. |

| so that | We take minutes SO THAT we have a record of the meetings. | |

| since | He took the train SINCE he did not want to drive. | |

| Contrast | but | I wanted to attend, BUT I was not able to. |

| although | ALTHOUGH it is a small project, it is an important one. | |

| while | Chapter 6 summarises key findings from earlier reports WHILE Chapter 7 focuses on the progress made since those reports were distributed. | |

| despite | Much remains to be done DESPITE significant improvements made since the last evaluation. |

You can create good sentences by working out how the various ideas relate to each other, selecting your main idea and choosing an appropriate way of putting the ideas together to reflect their relationship. If there isn't a relationship between the ideas don't put them in the same sentence. Also, don’t feel that you must always use this type of sentence. When the connection is clear, two simple sentences can convey the idea powerfully.

Activity 6: Putting ideas together

Combine the following groups of sentences into one or two sentences that clearly indicate the relationship between the ideas:

Example 1

- Changes made to the regulations are important.

- The changes include revisions to criteria for acceptance.

Changes made to the regulations are important since they include revisions to the criteria for acceptance. [Note that rather than repeating “the changes,” the pronoun “they” is used.]

Example 2

- Awareness of the problem has been raised.

- Much work still needs to be done to address the problem.

Although awareness of the problem has been raised, much work still need to be done to address it.

Example 3

- Good practices and success stories are being documented.

- The reason they are being documented is because they can have a multiplier effect.

- They can affect other departments.

- They can affect other organisations.

Good practices and success stories are being documented since they can have a multiplier effect, not only in other departments but also in other organisations.

Ordering ideas within sentences

It is the writer's job to make reading as easy as possible for the reader. In work-related writing, it is important to make the main point of the sentence easy to find and any conditions or qualifications clearly subordinate. Have a look at the following example that makes too much use of subordinating and coordinating words.

Because personal and social development of individuals and the benefits to society from lifelong learning should be highlighted, this report argues that the national government should establish a national qualifications’ framework to facilitate lifelong learning and to realise other objectives, which several state governments support while pointing out that there are other principal factors underpinning the establishment of the national qualifications’ framework.

Personal and social development of individuals and the benefits to society from lifelong learning should be highlighted. , this report argues that the national government should establish a national qualifications’ framework to facilitate lifelong learning and to realise other objectives. Various state governments support , but point out that there are other principal factors underpinning the establishment of the national qualifications’ framework.

As a result – takes the place of “because”, indicating the causal link between the first sentence and the second.

This – refers to the idea of the national government establishing a qualifications’ framework.

As the writer, it’s important that you balance the value of connecting words to indicate relationships with the dangers of sentences that become unwieldy and difficult to read. Variation in sentence length helps keep readers’ attention; an endless string of long sentences may exhaust them and discourage them from continuing.

Parallel structure

Parallel structure, the use of like constructions for like ideas, is very important for your reader. It is a great aid for giving your writing force and clarity. Parallel structure is particularly noticeable in lists and bulleted points; poor parallel structure makes them very difficult to read.

Below, on the left, you will see examples where parallel ideas are not reflected by parallel grammatical structure.

| POOR | BETTER |

|---|---|

| In this module, you will learn both editing and to proofread. | In this module, you will learn both editing and proofreading. |

| He took a new job as coordinator and taking minutes. | He took a new job as coordinator and minute taker. |

Daily duties include:

|

Daily duties include:

|

The Department priorities for the following period include:

|

The Department priorities for the following period include:

|

If you are not sure if you have achieved good parallel structure, look first at the verb forms. As you have likely noticed in the examples above, the differing verb forms in the first column make reading more difficult.

Activity 7: Parallel structure

Use parallel structure to improve the following examples.

Example 1:

The association was set up to represent, at the national level, the interests of all local authorities and encouraging the development of a culture of partnerships between local and central authorities.

The association was set up to represent, at the national level, the interests of all local authorities and to encourage the development of a culture of partnerships between local and central authorities.

Example 2:

I am enclosing both the interim narrative/financial reports for March, along with a mission report about the trip to Thailand. As well, I have enclosed a detailed expenditure report.

I am enclosing three reports:

- interim narrative/ financial report for March;

- mission report for Thailand trip;

- detailed expenditure report.

Example 3:

She is fast, efficient and a supervisor of great effectiveness.

She is a fast, efficient and effective supervisor.

Assignment preparation task 6: Clarity

What have you discovered about the clarity of your writing?

- How do you put your sentences together?

- Do you use parallel structure correctly?

Consider these points and make some notes about the sections you have just finished. This will help you when you complete Assignment 1A.

Also, note that you will need two examples of parallel structure from your own work for Assignment 1B. These examples can demonstrate times when you have used parallel structure correctly or times when you have not.

Paragraph and document flow

Now that you have considered good practice for developing sentences, let’s move to the next level of organisation: the paragraph.

Paragraphs help both readers and writers. They give readers a framework to use to make sense of the ideas writers are trying to communicate. They give you, the writer, a means of systematically developing the ideas you want to get across, connecting evidence and supporting ideas to your main idea. Each paragraph should develop a specific idea that supports your statement of purpose.

There is no ideal length for a paragraph. Paragraphs are effective because they work to support an idea, not because they have a particular number of words or sentences.

Good paragraphs use three important techniques to guide the reader:

- A good paragraph has a topic sentence that presents the main idea of the paragraph.

- The topic sentence contains a controlling idea. The other sentences in the paragraph work together to support this controlling idea.

- An effective paragraph follows a pattern of organisation that is easily recognisable. There are many patterns available to writers. We will be looking at a few of them in the following pages.

In the next few sections, you’ll work through examples of paragraphs from Council of Europe documents.

Activity 8: Identifying paragraphs

Look at the following letter and consider how you would break it into paragraphs. Then click the buttons to see how the same letter is divided into paragraphs. Do you notice a difference in the readability of the letter? Pay particular attention to the length of the paragraphs. For an e-mail like this one, using short paragraphs is effective and appropriate.

Dear Anna,

You have been accepted into Writing Effectively for the Council of Europe, and I am now providing you with more information in addition to the e-mail you received. Please find your welcome package attached including the acceptance letter, key dates and course regulations. These documents contain important information about the course. Please take the time to read through them carefully now before starting the course. Your assigned tutor will contact you by the course start date. I wish you success in this course!

Sincerely,

XXX

Course Coordinator

Dear Anna,

You have been accepted into Writing Effectively for the Council of Europe, and I am now providing you with more information in addition to the e-mail you received. Please find your welcome package attached including:

- Acceptance letter

- Key dates list

- Course regulations

These documents contain important information about the course. Please take the time to read through them carefully now before starting the course.

Your assigned tutor will contact you by the course start date.

I wish you success in this course!

Sincerely,

XXX

Course Coordinator

Topic sentences

A topic sentence contains the main idea or theme of the paragraph. If you had time only to read one sentence in a paragraph the topic sentence would give you the essence or main thrust of that paragraph. Skilled readers look for topic sentences to grasp general meaning quickly. A clear and well-placed topic sentence in each paragraph helps to make your work more accessible.

For workplace writing, the best position is usually right at the beginning of the paragraph. This position helps your reader the most and enables those who are too busy to read the whole document to skim through it and capture the main ideas.

Examples

Look at the following topic sentences in two simple examples:

- This new system causes problems for our staff members in several ways. Many are operating on computing equipment that is past due for an upgrade. Using the system requires training that many staff members are currently unable to access.

Notice how the second and third sentences are enumerating the problems the writer mentions in the topic sentence.

- Project reports must be done on time, and they must be consistent. When reports are late, they make it difficult for managers to balance competing staff requirements. When they are inconsistent in format, they take an unnecessarily long time to read.

Here again, the second and third sentences provide supporting reasons for the topic sentence.

Activity 9: Predict the paragraph

Now take a look at the following topic sentences. By reading these sentences, you should be able to guess what the rest of the paragraph will include. After you read the topic sentence, write down what you expect the paragraph to cover in the text area to the right (jotting down just a few words in point form is fine). Then reveal the rest of the paragraph to see if your assumptions about the paragraph were correct.

Example 1:

Children have rights.

Your Notes

Children have rights. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child recognises children as holders of many essential rights. In Europe, children’s fundamental rights are further protected by the European Convention on Human Rights and the European Social Charter. Just a few examples of these are: the right to life, the right not to be submitted to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, protection against forced labour or slavery, respect for private and family life, the right to protection from danger and the right to education.

Example 2:

The project aims to support member states in improving the health of their populations as an essential condition for social cohesion.

Your Notes

The project aims to support member states in improving the health of their populations as an essential condition for social cohesion. To that end, the project will promote citizens' health education and health literacy, including health information exchanges through internet, social networking and other interactive fora. Health literacy is the capacity to make sound health decisions in the context of everyday life and is a critical empowerment strategy to increase people's control over their health, their ability to seek out information and their ability to take responsibility.

Example 3:

The Congress is committed to the ONE in FIVE campaign to stop sexual violence against children and is working hard to raise awareness of local and regional authorities of the role they can play in combatting child sexual exploitation and abuse.

Your Notes

The Congress is committed to the ONE in FIVE campaign to stop sexual violence against children and is working hard to raise awareness of local and regional authorities of the role they can play in combatting child sexual exploitation and abuse. In particular, we have just launched a Pact of Towns and Regions to Stop Sexual Violence against Children. Our Pact contains examples of policies, activities, initiatives and structures which we feel local and regional authorities can usefully implement to achieve the aims of the campaign. It follows the four-pronged approach of Prevention, Protection, Prosecution and Participation: to prevent abuse, protect victims, prosecute perpetrators and ensure the full participation of children in the entire process. Thanks to this approach, local and regional authorities can decide how best to run public sector agencies to ensure that children and young people are protected and supported whilst actively pursuing the prosecution of perpetrators. We are, of course, aware that in these times of economic and financial crisis, money is tight, cuts are being made, transfers to local and regional councils are being reduced. This is why the Pact also proposes a number of simple initiatives that require very little if any public spending – for example simply putting a link on towns’ homepages to the Council of Europe ONE in FIVE website. The ultimate aim is, of course, to encourage local and regional authorities to adopt specific strategies and set up dedicated structures, such as children’s houses or multidisciplinary centres, which will obviously necessitate substantial investment.

As a reader, as soon as you read the topic sentence, you develop a set of expectations about the kind of information the paragraph will contain. Your reader develops these expectations too, based on your topic sentences. It is your job as a writer to fulfil the reader's expectations. If you set up reader expectations that you do not fulfil your document will be incoherent. Your reader will have difficulty understanding your message and is unlikely to give you your desired response.

Controlling ideas

Good topic sentences contain a controlling, or defining, idea. This idea tells the reader how the paragraph is held together. It indicates the structure of the paragraph in order to help the reader comprehend the relationship between the various sentences in the paragraph.

In the paragraph on the previous page about the rights of children, the topic sentence is:

In this case, that is also the controlling idea: children have rights.

Look again at the complete paragraph to see how these words control and order the content of the paragraph. You’ll notice right away that the paragraph focuses on the way those rights are protected, as well as definitions of the rights themselves. In this paragraph, the writer chose to focus first on the protections to children’s rights that exist in Europe and then on the rights themselves. These two sections could have been reversed; both support the topic sentence, but in different ways.

Children have rights. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child recognises children as holders of many essential rights. In Europe, children’s fundamental rights are further protected by the European Convention on Human Rights and the European Social Charter. Just a few examples of these are: the right to life, the right not to be submitted to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, protection against forced labour or slavery, respect for private and family life, the right to protection from danger and the right to education.

The controlling idea answers the question, “What is this paragraph about?” Ensuring that the paragraph is about one controlling idea helps keep the reader on track; it also helps keep you as the writer on track, helping you to identify what does and does not belong in the paragraph.

Activity 10: Identifying controlling ideas in topic sentences

You will analyse the same paragraphs you read when you were predicting content based on the topic sentence. Now, look for the controlling idea in each topic sentence.

Copy the word or phrase that reveals the controlling idea of the paragraph and paste it in the space below. This controlling idea will be part of the topic sentence.

Click on the Show Solution buttons to check your answers.

Example 1:

The project aims to support member states in improving the health of their populations as an essential condition for social cohesion. To that end, the project will promote citizens' health education and health literacy, including health information exchanges through internet, social networking and other interactive fora. Health literacy is the capacity to make sound health decisions in the context of everyday life and is a critical empowerment strategy to increase people's control over their health, their ability to seek out information and their ability to take responsibility.

The controlling idea is improving the health of their populations. The rest of the paragraph talks about the ways in which this is done and provides a definition of one of the important terms.

Example 2:

The Congress is committed to the ONE in FIVE campaign to stop sexual violence against children and is working hard to raise awareness of local and regional authorities of the role they can play in combatting child sexual exploitation and abuse. In particular, we have just launched a Pact of Towns and Regions to Stop Sexual Violence against Children. Our Pact contains examples of policies, activities, initiatives and structures which we feel local and regional authorities can usefully implement to achieve the aims of the campaign. It follows the four-pronged approach of Prevention, Protection, Prosecution and Participation: to prevent abuse, protect victims, prosecute perpetrators and ensure the full participation of children in the entire process. Thanks to this approach, local and regional authorities can decide how best to run public sector agencies to ensure that children and young people are protected and supported whilst actively pursuing the prosecution of perpetrators. We are, of course, aware that in these times of economic and financial crisis, money is tight, cuts are being made and transfers to local and regional councils are being reduced. This is why the Pact also proposes a number of simple initiatives that require very little if any public spending – for example simply putting a link on towns’ homepages to the Council of Europe ONE in FIVE website. The ultimate aim is, of course, to encourage local and regional authorities to adopt specific strategies and set up dedicated structures, such as children’s houses or multidisciplinary centres, which will obviously necessitate substantial investment.

The controlling idea is campaign to stop sexual violence against children. Note that the controlling idea is the campaign, rather than stopping the violence. The paragraph provides details about the campaign and campaign finances that would not be relevant unless the campaign itself was the focus.

Organising a paragraph

There are many ways to develop paragraphs. It's the writer's job to make sure that the structure or organisation of the paragraph is made clear to the reader. Have a look at the following types of paragraph structure. This is not an exhaustive list but it does give an indication of the variety of paragraphs that you can compose.

Chronological

Begin with what happened first and take it from there.

The Council of Europe is one of the oldest international organisations dedicated to fostering co-operation in Europe through the promotion of human rights, democracy and the rule of law. Founded in 1949 by the Treaty of London, it was established by a group of national leaders to ensure that the horror and suffering of the 20th century’s two world wars would never be repeated. Since then, the ten original members (Belgium, Denmark, France, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom) have been joined by almost all of Europe’s other countries, and the Council now has 47 member states.

Click to see how the progression of time shapes the paragraph.

Yellow highlighted words are associated with the passage of time. Blue highlights the controlling idea in the bolded topic sentence.

The Council of Europe is one of the oldest international organisations dedicated to fostering co-operation in Europe through the promotion of human rights, democracy and the rule of law. Founded in 1949 by the Treaty of London, it was established by a group of national leaders to ensure that the horror and suffering of the 20th century’s two world wars would never be repeated. Since then, the ten original members (Belgium, Denmark, France, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom) have been joined by almost all of Europe’s other countries, and the Council now has 47 member states.

Classification

Provide examples of the claim made in the topic sentence or list examples of the subject.

The European Committee for the Prevention of Torture (CPT ) organises visits to places of detention in order to assess how persons deprived of their liberty are treated. These places include prisons, juvenile detention centres, police stations, holding centres for immigration detainees, psychiatric hospitals, social care homes, etc.”

Click to see the relationship between the topic sentence and the paragraph.

The blue highlighted area is the controlling idea. The yellow highlighted items are examples of places of detention. The topic sentence is bolded.

The European Committee for the Prevention of Torture (CPT) organises visits to places of detention in order to assess how persons deprived of their liberty are treated. These places include prisons, juvenile detention centres, police stations, holding centres for immigration detainees, psychiatric hospitals, social care homes, etc.”

Definition

Arrange the information around a definition.

When the Court receives an application, it may decide that a State should take certain measures provisionally while it continues its examination of the case. This usually consists of requesting a State to refrain from doing something, such as not returning individuals to countries where it is alleged that they would face death or torture.

Click to see the relationship between the topic sentence and the paragraph.

The yellow highlighted items are elements of the definition of provisional measures, which is the controlling idea (highlighted in blue).

When the Court receives an application, it may decide that a State should take certain measures provisionally while it continues its examination of the case. This usually consists of requesting a State to refrain from doing something, such as not returning individuals to countries where it is alleged that they would face death or torture.

Contrast and comparison

Demonstrate similarities or differences between two or more people or things.

The economic recovery observed in the OECD area since 1995 is holding firm in some countries such as the United States while slackening, sometimes considerably, in others, especially in Mexico and several European countries. Growth in the OECD area was 2.9% in 1994, slowed to around 2% in 1995, and was forecasted to remain at that level in 1996. By contrast, world merchandise trade grew by almost 10% in 1994 and by 8.5% in 1995 and was forecasted to slow further to around 7% in 1996.

Click to see the relationship between the topic sentence and the paragraph.

The blue highlighted items combine to make the controlling idea. The yellow highlighted areas reveal how the comparison is structured using transition words and phrases that indicate similarity or contrast.

The economic recovery observed in the OECD area since 1995 is holding firm in some countries such as the United States while slackening, sometimes considerably, in others, especially in Mexico and several European countries. Growth in the OECD area was 2.9% in 1994, slowed to around 2% in 1995, and was forecasted to remain at that level in 1996. By contrast, world merchandise trade grew by almost 10% in 1994 and by 8.5% in 1995 and was forecasted to slow further to around 7% in 1996.

Ask and answer a question

Use a question as the topic sentence.

What are the “child-friendly justice” guidelines about? They apply to everyone under 18 whenever they come into contact with the justice system, such as when they break the law, when their parents get divorced or when someone who has hurt them is being punished. The guidelines are designed to help governments make sure that children’s rights are protected whenever decisions concerning children are made.

Click to see the relationship between the topic sentence and the paragraph.

The blue highlighted area identifies the controlling idea. The yellow highlighted areas refer to the details provided to explain the idea.

What are the “child-friendly justice” guidelines about? They apply to everyone under 18 whenever they come into contact with the justice system, such as when they break the law, when their parents get divorced or when someone who has hurt them is being punished. The guidelines are designed to help governments make sure that children’s rights are protected whenever decisions concerning children are made.

Induction

Infer a general principle from a line of reasoning.

Some critics of the MEDICRIME Convention have claimed that it lacks political legitimacy simply because it was negotiated in a regional, European framework. These critics would like States in other parts of the world to ignore the MEDICRIME Convention and instead wait for a possible UN convention on false/counterfeit medical products to be drafted, negotiated and adopted. The answer to this criticism is rather straightforward: the counterfeiting of medicines has developed into an industry that kills hundreds of thousands of people a year. Counterfeit medicines affect 10% of the world medicines market and the resulting losses are estimated at about 500 billion euros a year. Every step taken in the fight against cynical criminals who make a fortune on the sufferings of their fellow human beings is a valuable one. Surely, the measures taken in this regard by Europe can be equally useful for States in other parts of the world.

Click to see the relationship between the topic sentence and the paragraph.

The highlighted areas are examples of reasons to support criminalisation. Note that when a paragraph is organised this way, the topic sentence is usually last.

Some critics of the MEDICRIME Convention have claimed that it lacks political legitimacy simply because it was negotiated in a regional, European framework. These critics would like States in other parts of the world to ignore the MEDICRIME Convention and instead wait for a possible UN convention on false/counterfeit medical products to be drafted, negotiated and adopted. The answer to this criticism is rather straightforward: the counterfeiting of medicines has developed into an industry that kills hundreds of thousands of people a year. Counterfeit medicines affect 10% of the world medicines market and the resulting losses are estimated at about 500 billion euros a year. Every step taken in the fight against cynical criminals who make a fortune on the sufferings of their fellow human beings is a valuable one. Surely, the measures taken in this regard by Europe can be equally useful for States in other parts of the world.

Deduction

The opposite of induction, this paragraph moves from the general to the particular. The topic sentence introduces the general idea, which is then followed by details and a conclusion.

Counterfeiting of medical products and similar crimes need to be criminalised because of the risk they represent for public health. The treatment of disease is delayed because of the ineffectiveness of counterfeit medicines and illegal products and the proper treatment may be rendered useless because it is taken too late. Counterfeit medical products and similar crimes are silent killers because the patient will die from the underlying disease as a result of ineffective treatment. In such cases, nobody will look for counterfeiting as a possible cause.

The highlighted items reveal the evidence used to support the controlling idea of the need to criminalise counterfeit medical products.

The highlighted items reveal the evidence used to support the controlling idea of the need to criminalise counterfeit medical products.

Counterfeiting of medical products and similar crimes need to be criminalised because of the risk they represent for public health. The treatment of disease is delayed because of the ineffectiveness of counterfeit medicines and illegal products and the proper treatment may be rendered useless because it is taken too late. Counterfeit medical products and similar crimes are silent killers because the patient will die from the underlying disease as a result of ineffective treatment. In such cases, nobody will look for counterfeiting as a possible cause.

Headings versus topic sentences

In many documents, headings are used to alert the reader to the main idea of the paragraph or section. The same rules apply: you still need a topic sentence to make the main idea clear, and all sentences in the paragraph should contribute to the main idea. You still need some kind of controlling idea in the text to help the reader understand how the sentences or points relate to each other. The heading serves as an alert, but in most cases, it cannot replace a topic sentence.

Neither do headings eliminate the need for a pattern of organisation in the paragraph. Layout and use of devices such as bullet points, however, can be used to reveal the pattern.

| TOPIC SENTENCE | HEADING |

|---|---|

| The new guidelines have many shortcomings and are poorly presented. | Problems in New Guidelines |

| The delegates have been selected from three different areas. | Delegate Selection |

| The CEB’s principal activity consists of granting loans that enable part-financing of economically and socially viable projects. | Part-financing of Viable Projects |

Headings and subheadings should help your readers skim the document. They should make sense on their own and be informative.

Activity 11: Writing headings and topic sentences

Look at the following two paragraphs. Both are missing their topic sentences. Write an appropriate sentence for each and provide a heading that reflects the meaning behind the topic sentence that you write.

Paragraph 1

Staff may fear changes in their functions, transfers or even termination of the contractual relationship. The stress is particularly severe for those having short-term contract arrangements. The negative effects on staff of rumours and misinformation can be avoided by the responsible manager directly advising staff, at the earliest opportunity, of any proposals or decisions for change.

Your Topic Sentence

Original topic sentence: Failure to share information with staff in a timely manner can lead to anxiety, frustration and low morale.

Possible heading: The Importance of Sharing Information

Paragraph 2

It touches some of our deepest instincts, including ideas of revenge, honour, hatred and fear. When we hear of a particularly vicious crime or are close to the victim of a brutal act, we naturally have intense reactions, which could include wanting to see the perpetrator put to death. Many people across the continent still feel that the death penalty would be an acceptable response to particularly barbarous acts, and there are of course some countries in the world where the death penalty still exists.

Your Topic Sentence

Original topic sentence: The death penalty is a very emotive issue.

Possible heading: The Death Penalty: Intense Reactions

Paragraph and document flow

Paragraphs with flow are easier for the reader to follow. In documents, effective flow comes when each paragraph seems to flow on from the one before and where the relationship between the paragraphs is perfectly clear. In paragraphs with flow, each sentence flows from the one before in a discernible pattern. The topic sentence and controlling idea give the roadmap for the paragraph. Coherence within a paragraph is achieved by skilful use of:

- transitional words and phrases;

- pronoun references;

- repeated words;

- parallel construction.

Roma housing situations are very diverse. Some families have been settled for several centuries in one area and live in bungalows, small houses or apartments. Others live in a caravan or mixed accommodation (house and caravan or mobile-home) although horse-drawn caravans are now rare. Some families live in very cramped social housing.

The controlling idea is clearly expressed in the topic sentence. The use of the words “some” and “others” in the paragraph signal to the reader that the paragraph is talking about a variety of situations, but that there may be more that are not discussed.

Housing conditions therefore depend very much on the immediate surroundings, the attitude towards them of the neighbouring populations and the sometimes-stringent regulations which mean that the Roma have to limit the time they can remain in one place.

This short paragraph summarises what has gone before, referencing it with the transitional word “therefore”, and introduces new complexity to the situation.

There are many Roma families in Europe who are obliged to live in shanty towns, on the pavements in cities, alongside motorways and industrial estates in makeshift housing made from recycled material, with no drinking water, electricity or means of disposing of waste. Roma families wising to engage in an itinerant life have extreme difficulty finding suitable unpolluted sites, not too far away from schools, obliging them to camp illegally or be continually on the move.

The third paragraph touches back to the first one, where “some” and “others” were discussed, to tell the reader about “many”. This is satisfying for the reader, who now seems to be getting the full picture of the situation.

Transitional words and phrases

This list of transitional words and phrases is classified according to different kinds of markers.

| Type of marker | Example |

|---|---|

| Semantic markers. They indicate how ideas are being developed. | firstly; secondly; finally |

| Markers for illustrations and examples | for instance; for example |

| Markers that introduce an idea that runs against what has been said earlier | but; nevertheless; yet; although; by contrast; however |

| Markers showing a cause and effect relationship between one idea and another | so; therefore; because; since; thus; consequently; for this reason |

| Markers that show the writer's intention to sum up the message | to summarise; in other words; it amounts to |

| Markers indicating the relative importance of different items | it is worth noting; it is important to note that; the next crucial point is |

| Markers used to rephrase what has already been said | in other words; put differently; that is to say |

| Markers that express a time relationship | then; next; after; while; when |

Activity 12: Developing paragraphs

Rearrange the following sentences into a logically developed paragraph. Use the transition words to help you find the correct order.

Paragraph 1

- To be successful in a job interview, you should demonstrate certain personal and professional qualities.

- Furthermore, you must make such a positive impression that the interviewers will remember you while they are interviewing other applicants.

- And finally, if you really want to impress you must convey a sense of self- confidence and enthusiasm for work.